strategy+business, March 19, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

About an hour into Still on the Run, a documentary exploring the career of rock guitar god Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, another deity in the pantheon, pops up on screen and says, “I don’t even know how he’s doing it half the time.” Clapton is talking about Beck’s ability to give voice to the guitar. But his comment set me to wondering how Beck developed his unique style and what, if any, lessons his nearly 60-year career might offer those who aspire to reach the top of the business world.

With CEO tenure in large companies running five years or so, the fact that Beck has been numbered among the world’s best guitarists for about 10 times that long is worth exploring. Surely, innate talent and endless hours of practice count for a lot. But loads of guitarists have both, and haven’t had careers that lasted as long as the average CEO’s. Beck, however, has been an inveterate seeker of innovation in both technology and technique. And this habit has enabled the 74-year-old London-born musician to continuously expand his capabilities and transform his sound.

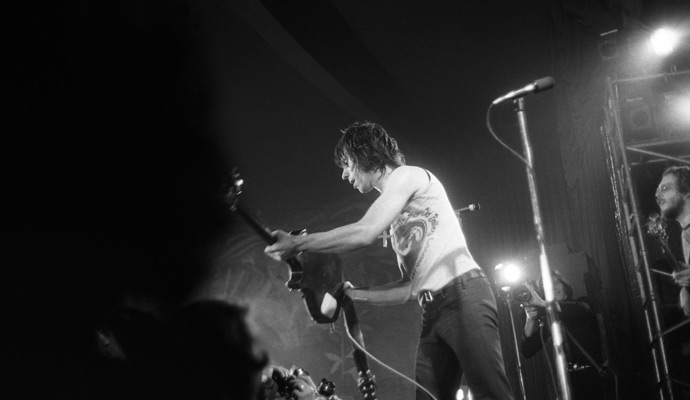

Jeff Beck performs at the Bataclan in Paris in 1973.

Photograph by Philippe Gras / Alamy

As biographer Martin Power tells it in Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck (Omnibus Press, 2014), Beck’s parents valued musicianship, but not the electric guitar, which in the 1950s was associated with rockabilly and other disreputable musical genres. When his parents refused even to spring for new strings for a borrowed guitar, the teenager began building his own crude instruments. Unable to tune his early efforts, Beck learned to bend the strings to pitch while playing, a work-around that became a signature. The wannabe lead guitarist stole the pickup needed for his first electric guitar and built its amp in his school’s science department. Since then, Beck continually explored and adopted technological advances in guitar effects and electronics — such as tape-delay units, fuzz boxes, and guitar synthesizers — to shape and extend his playing.

Beck’s eagerness to learn and incorporate techniques from far-flung places is another hallmark of his career. Like Clapton, he learned from American blues giants — and rode the wave of cultural appropriation that gave rise to rock and roll. According to Power’s biography, Beck says that the first time he heard Jimi Hendrix play, he thought, “Oh, Christ, all right, I’ll become a postman.” Then he followed Hendrix around to learn how he created his sound. Other inspirations include a women’s choir that recorded Bulgarian folk songs, operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti, and electronic dance music. Beck describes his resulting style as “a form of insanity…. A bit of everything, really. Rockabilly licks, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, all the people I’ve loved to listen to over the years. Cliff [Gallup], Les [Paul], Eastern and Arabic music, it’s all in there.” Read the rest here.

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Leadership lessons from a guitar hero

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:12 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: creativity, innovation, leadership, personal success, work

Saturday, March 2, 2019

Finding your company’s cultural sweet spot

strategy+business, March 1, 2019

strategy+business, March 1, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast” is a pretty tasty bon mot, though it’s doubtful that Peter Drucker, who usually gets credit for it, actually cooked it up. It can also cause severe indigestion when leaders ignore it. If you’re tempted to join them, read Rule Makers, Rule Breakers, by University of Maryland, College Park, psychology professor Michele Gelfand.

Gelfand has been studying culture and social norms for more than 20 years. Ever wonder why conjuring up a “burning platform” galvanizes workers instead of sending them scurrying for the exit doors? It’s the same reason that the heartbeats of firewalkers in the Spanish village of San Pedro Manrique, as well as the people watching them, become synchronized. It’s also why test subjects who eat fiery chili peppers together report a higher sense of bonding, and work better together in subsequent economic games. “Social norms, like participating in rituals, can increase group cohesion and cooperation,” says Gelfand.

Social norms are the glue that holds groups together. “They give us our identity, and help us coordinate in unprecedented ways,” Gelfand writes. “Yet cultures vary in the strength of their social glue, with profound consequences for our worldviews, our environments, and our brains.” And for companies, too. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:26 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, corporate life, corporate success, human resources, innovation, management, org culture, work

Friday, March 1, 2019

Two Capabilities for Building Organizational Agility

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

Boss Magazine, March 2019

by David Mallon

A few years ago, agility was considered a competitive advantage — a trait that a company could develop and nurture to get a leg up in its industry and markets. But late last year, when Forbes Insights conducted a survey of 1,000 executives across industries and geographies, 81 percent of them identified organizational agility as the most important characteristic of a successful organization. Today, agility isn’t about raising the competitive stakes; it’s an organizational trait needed to get into the game.

At its core, agility is simply the ability to change direction quickly in response to external conditions. The problem, of course, is that for the past century, people have been building companies that were anything but agile.

How can you make your company more agile? Focus your efforts on developing the two capabilities that define the trait: sense and response. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:14 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: articles to ponder, change management, corporate life, corporate success, human resources, transformation, work