strategy+business, January 10, 2023

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Tom Werner

If you’ve been feeling like your leadership contributions are underappreciated, add a copy of Why Managers Matter to your reading list. In it, Nicolai Foss, a strategy professor at the Copenhagen Business School, and Peter Klein, the W.W. Caruth Chair and professor of entrepreneurship at the Hankamer School of Business, Baylor University, examine the various iterations of manager-free organizations that have been proposed—and occasionally adopted—over the past 50 years or so. Their conclusion: nonsense!

Foss and Klein lump the ideas of management thinkers, such as Gary Hamel, Michele Zanini, and Frederic Laloux, and approaches to decentralized management, such as holacracy and agile, into what they call the bossless company narrative. “The basic thrust of the genre is that while bosses are still around, the less control they exercise the better,” they write. “What the Harvard historian Alfred D. Chandler Jr. called the ‘visible hand’ of management should give way to worker autonomy, self-organizing teams, outsourcing, and an egalitarian office culture.”

Then the duo bales the entire genre into something resembling a straw man and puts a match to it. “The near-bossless companies—and there aren’t many of them—with their self-managing teams, empowered knowledge workers, and ultra-flat organizations are not generally or demonstrably better than traditionally organized ones,” declare Foss and Klein. “Bosses matter, not just as figureheads but as designers, organizers, encouragers, and enforcers.”

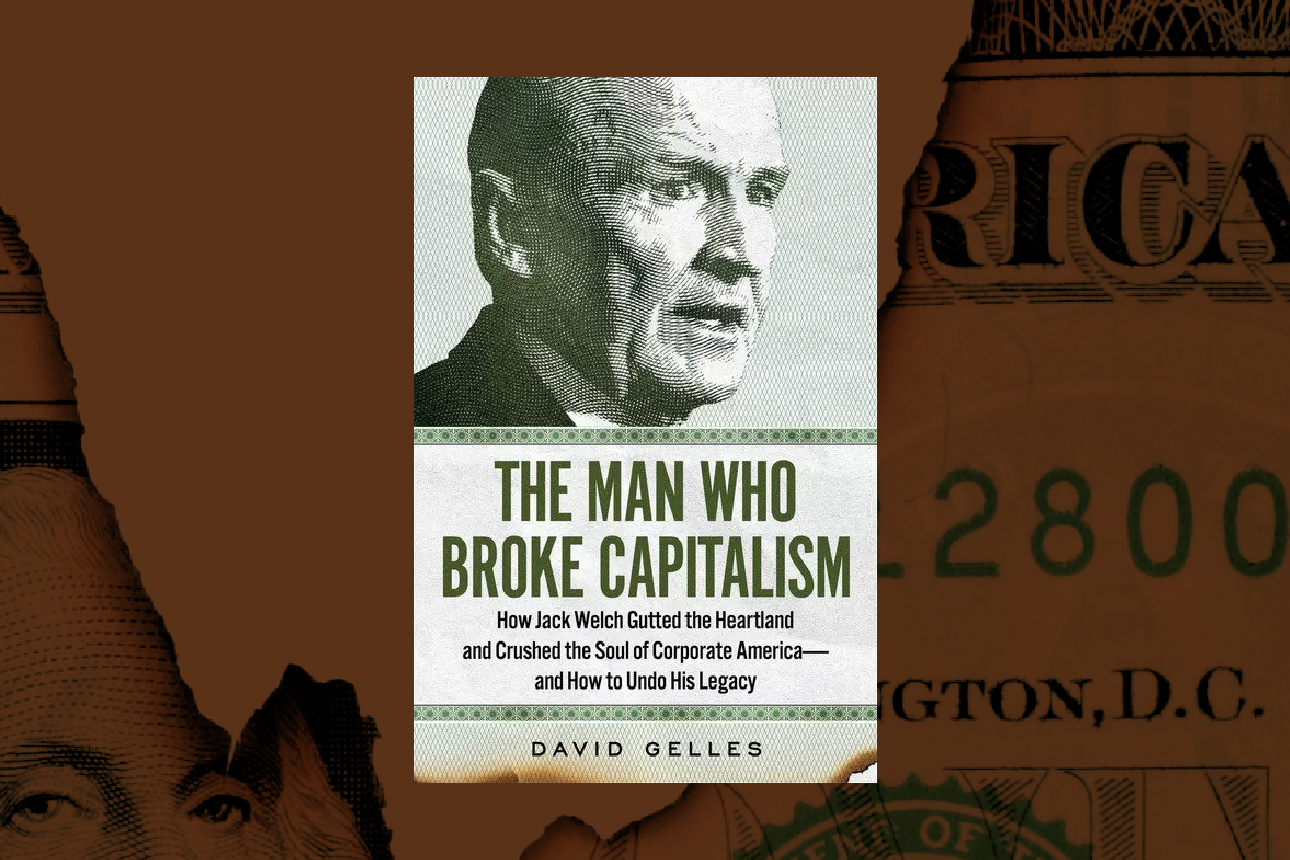

Foss and Klein make a detailed and extended case against the bossless company narrative with which it is hard to take issue, especially in the realm of large enterprises. Schemes like holacracy, in which decisions are made by teams, may work for small companies with distributed ownership, such as boutique consultancies and other kinds of partnerships, but they haven’t worked in large companies like Zappos, which have many more employees and require far more coordination. Agility, too, tends to work better for running projects than for running whole companies. In short, hierarchical management structures are, as the authors put it, “the worst form of organization—except for all the others.” Read the rest here.