strategy+business, June 5, 2023

by Theodore Kinni

Illustration by Luis Alvarez

As CEOs continue to call employees back to the office, their rationales often include remote work’s deleterious effects on innovation. There is some basis for these claims: a recent study found that the number of email exchanges between research units at MIT dropped by 38% during the pandemic lockdown. Its authors equated email volume with the weak ties that are crucial to the diffusion of information and ideas in networks, and thus concluded from the drop in traffic that remote work hinders innovation. But no matter how much weight you assign this finding, it’s a stretch to peg the success—or failure—of a company’s innovation efforts to the number of rears in seats.

The truth is innovation in large companies is a perennial challenge for leaders, no matter where employees are working. The late Clayton Christensen and other researchers detailed the obstacles to innovation that arise when industry-leading companies confront disruptive technologies. Large companies also struggle to transform innovation investments into financial results: in 2018, consultants from Strategy&, PwC’s global consulting business, examined 15 years of data drawn from the firm’s Global Innovation 1000 research—an annual analysis of the 1,000 publicly held companies that spend the most on R&D—and concluded, “There is no long-term correlation between the amount of money a company spends on its innovation efforts and its overall financial performance.”

So how can leaders move the innovation needle in big companies? I turned to Lorraine Marchand for answers. Marchand served in a variety of executive and board positions, including a former stint as general manager of the life sciences division of IBM’s Watson Health (now Merative), before writing The Innovation Mindset: Eight Essential Steps to Transform Any Industry — a practical guide to building innovation prowess across an organization — and founding her own innovation consultancy.

Here is her list of ways to make your company more innovative. Read the rest here.

Monday, June 5, 2023

How to move the needle on innovation

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:26 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: human resources, innovation, leadership, management, strategy+business

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

The Missing Discipline Behind Failure to Scale

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, April 12, 2023

by Andy Binns and Christine Griffin

Dan Page/theispot.com

Over the next few years, Best Buy Health tested its key assumptions about the opportunity, seeking out the sweet spot that would allow it to build a new business to sit alongside the company’s existing retail franchise. By 2022, it was a $525 million business, projected to grow at a 35% to 45% compound annual growth rate through 2027. The initiative created a new growth vector for its parent company and gave it a measure of resilience in the turbulent consumer retail sector.

Best Buy succeeded where many companies fail. It moved through the three innovation disciplines required to build new businesses: ideation, incubation, and scaling. It came up with a new idea for solving the customer problem of aging safely at home, incubated it by running in-market experiments to test value propositions, and then scaled it to a revenue-generating business unit. This is a relatively rare accomplishment. Our research finds that while 80% of companies claim to ideate and incubate new ventures, only 16% of companies successfully scale them.

A key contributor to this problem is the almost exclusive focus that companies place on the first two innovation disciplines. The ways and means of ideation and incubation — embodied in methodologies such as design thinking and lean startup, and disseminated by an army of trainers and consultants — are well known and readily available. However, when it comes to scaling, there are few methodologies to guide corporate decision-making.

Scaling is the missing innovation discipline. Indeed, when we assessed the innovation frameworks used by 15 large corporate incubation units, we found that only four mentioned scaling. For example, one large IT company’s incubation unit has a highly evolved process for ideation, validation, and incubation, but its framework stops at scaling. Scaling is considered outside the remit of such units: It becomes the kind of blind spot that author Douglas Adams characterized as “somebody else’s problem.” This leaves a critical gap in the ability of companies to build new businesses. After all, ideation and incubation generate value only when scaling succeeds.

To learn how to bridge this gap, we studied Best Buy and 30 other successful and unsuccessful corporate ventures. We found that most of the successful companies followed a similar approach to scaling new ventures that we call a scaling path. It requires a clarity of ambition; an understanding of the assets needed to access the customers, capabilities, and capacity required by the new business; and a willingness to use a variety of techniques to assemble those assets into a coherent strategy for attaining scale. Best Buy, for example, leveraged its existing assets — its stores, customers, and Geek Squad technical assistance team — and combined them with a $2.2 billion investment in acquisitions to scale its health business.

In this article, we offer five key lessons for building a scaling path that are drawn from both successful and unsuccessful corporate ventures. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

2:16 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, innovation, new ventures

Thursday, December 8, 2022

It’s Time to Take Another Look at Blockchain

MIT Sloan Management Review, December 8, 2022

Ravi Sarathy, interviewed by Theodore Kinni

It wasn’t long after the developers of bitcoin first used a distributed ledger to record transactions in 2008 that the blockchain revolution was announced with all the fanfare that usually accompanies promising new technologies. Then, as often happens with emerging technologies, blockchain’s promise collided with developmental realities.

Now, a decade and a half down the road, that early promise is becoming manifest. In his new book, Enterprise Strategy for Blockchain: Lessons in Disruption From Fintech, Supply Chains, and Consumer Industries, Ravi Sarathy, professor of strategy and international business at the D’Amore-McKim School of Business at Northeastern University, argues that distributed ledger technology has matured to the point of enabling a host of applications that could disrupt industries as diverse as manufacturing, medicine, and media.

Sarathy spoke with Ted Kinni, senior contributing editor of MIT Sloan Management Review, about the state of blockchain, the applications that are most relevant now for large companies, and how their leaders can harness the technology before established and new competitors use it against them.

MIT Sloan Management Review: Blockchain has been slow to gain traction in many large companies. What’s holding it back?

Sarathy: Blockchain is a complex technology. It is often secured by an elaborate mathematical puzzle that is energy intensive and requires large investments in high-powered computing. This also limits the volume of transactions that can be processed easily, making it hard to use blockchain in a setting like credit card processing, which involves thousands of transactions a second. Interoperability is another technological challenge. You’ve got a lot of different protocols for running blockchains, so if you need to communicate with other blockchains, it creates points of weakness that can be hacked or otherwise fail.

Aside from the technological challenges, there is the issue of cost and benefit. Blockchain is not free, and it’s not an easy sell. It requires significant financial and human resources, and that’s a problem because it’s hard to convince CFOs and other top managers to give you a few million dollars and a few years to develop a blockchain application when they do not have clear estimates of expected returns or benefits.

Lastly, there are organizational challenges. A blockchain is intended to be a transparent, decentralized network in which everyone talks to each other without any intermediaries organized in a world of hierarchies. Making that transition can require a long philosophical and cultural leap for traditional companies used to a chain of command. Trust, too, becomes a huge issue, particularly when you start adding independent firms to a blockchain. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:47 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbooks, blockchain, corporate success, innovation, technology

Thursday, August 25, 2022

How “Corporate Explorers” Are Disrupting Big Companies From the Inside

Insights by Stanford Business, August 24, 2022

by Theodore Kinni

|iStock/Alexey Yaremenko

The conventional wisdom holds that disruptive innovation is beyond the ken of large, incumbent companies. But then there are companies like Microsoft, which transformed its ubiquitous Office software suite into the Office 365 subscription service. “If Microsoft had done that as a startup, it would be a multi-unicorn,” says Andrew Binns, a founder and director of the strategic innovation consultancy Change Logic. “Office 365 is a whole new business model, but nobody talks about it as disruptive innovation.”

Binns, along with Charles O’Reilly, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and Michael Tushman of Harvard Business School, finds that more and more established companies are overcoming the obstacles to innovation with the help of what they call corporate explorers. Corporate explorers are managers who build new and disruptive businesses inside their companies. Sometimes with a formal mandate, sometimes not, they use corporate assets to support and accelerate the development of these new ventures.

Binns, O’Reilly, and Tushman studied a number of these entrepreneurial insiders and report their findings in The Corporate Explorer: How Corporations Beat Startups at the Innovation Game. The book builds on the trio’s continuing research into ambidextrous organizations — companies that succeed over the long haul by simultaneously exploiting their existing businesses and building new ones that drive future growth.

In a recent interview, O’Reilly and Binns described the traits of corporate explorers and the conditions they need to thrive. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

3:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbooks, corporate success, entrepreneurship, innovation, Insights by Stanford Business, strategy, transformation

Thursday, June 30, 2022

Accelerating digital: A win-win-win for customer experience, the environment and business growth

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand on this report:

Economist Impact, June 2022

Digitally advanced firms are accelerating ahead of the competition. They are able to use real-time data insights to transform customer experiences and to improve their sustainability footprint. Discover how businesses can overcome data access and activation challenges to drive profitable growth.

The business landscape is constantly evolving and, with it, digital transformation. Businesses are under pressure to adapt to new competitors, increasingly from non-traditional markets, and to navigate ongoing geopolitical and economic uncertainty. At the same time, they need to become more sustainable and socially responsible, driven by government mandates and customer demands. Our new study shows that digitally driven businesses are able to embrace these rapid changes in their markets and deliver better customer experiences to drive profitable growth.

Indeed, the vast majority of firms we surveyed (99%) are leveraging new digital business models to tackle these challenges and drive greater agility, a trend that has been accelerated by covid-19. Over half (55%) of businesses expect a long-term increase in their use of digital technologies as a result of the pandemic, according to research by the European Investment Bank.

Firms that are able to capture and derive value from new streams of data, and offer new products and services rooted in digital capabilities, can improve their operational efficiency, reduce their carbon footprint and boost customer satisfaction. This can translate into improvements in both revenues and profit margins, with 80% of our survey respondents stating that some form of digital transformation contributes over half of their profits today. Moreover, 95% expect some, most, or all of their revenue to be digitally enabled within five years.

However, there is often a wide gulf between the digital ambitions of firms and their ability to use data insights at scale, which would enable employees to make better real-time decisions and drive higher levels of innovation.

To better understand these trends, Economist Impact has undertaken an ambitious research programme. We have examined the state of digital transformation in businesses across five sectors in which digitalisation offers substantial opportunities for growth and competitive advantage: construction and infrastructure; manufacturing; transportation and logistics; energy; and healthcare and pharmaceuticals. Our global survey of 500 multinational firms identifies the ongoing barriers they face in executing their digital strategies. We offer cross-industry insights on how these barriers are being overcome based on economic analysis of firms that are successfully using digital business models to boost their customer satisfaction, sustainability metrics and revenues, and interviews with experts. Read and download the report here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:49 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, digitization, innovation, management, platforms, technology, transformation

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

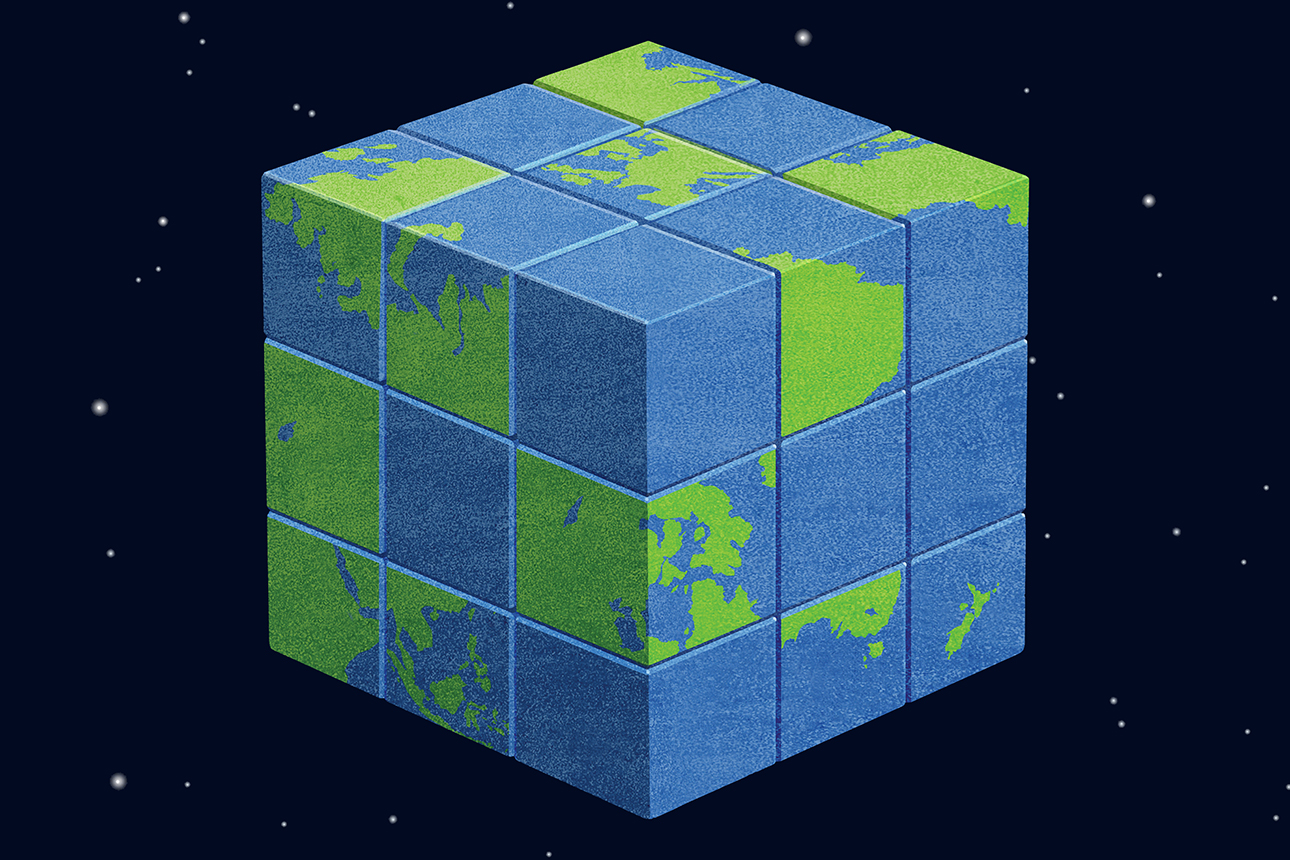

Think Globally, Innovate Locally

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, February 23, 2022

by Satish Nambisan and Yadong Luo

Michael Glenwood Gibbs/theispot.com

Digitization and globalization are converging to transform innovation in multinationals across industries. Companies such as Bayer Crop Science, John Deere, Johnson Controls, Philips, and Unilever are pursuing the promise of what we call digital globalization. They are finding that digitally infused innovation assets, such as data, content, product components, tools, and processes, are not only readily portable across national borders but also amenable to mixing and matching. This digitally enabled innovation generates new offerings, business models, and operations to suit specific country markets — at a faster pace and lower cost than previously.

Fashion brand Tommy Hilfiger has deployed a fully digital design workflow across all of its global apparel design teams. Designers catering to the demands of different markets around the world can create, store, share, and reuse digital design assets. Transforming traditional design and sample production steps into such digital-infused processes enables the label to not only accelerate its innovation but also diversify its offerings.

As promising as digital globalization sounds, however, it is facing headwinds that are driving deglobalization (or localization), including trade restrictions and uncertainties fueled by geopolitical tensions and nationalism. China, for instance, recently passed a host of protectionist laws and regulations aimed at controlling the internet and cross-border data flows. As companies such as Apple, Morgan Stanley, and Oracle have discovered, there is ambiguity around what constitutes personal data and what should be localized in China. This is significantly limiting the portability of multinational companies’ digital innovation assets and raising the level of innovation uncertainty and risk. Geopolitical tensions can also result in more closed and less trusting stances when companies pursue collaborative innovation ventures.

Thus, for multinationals, the coexistence of globalization and localization creates a challenging context for innovation. How, then, can they pursue innovation to take advantage of the forces driving digital globalization while also adapting to the forces driving localization? Read the read here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:11 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, corporate success, digitization, globalization, innovation

Thursday, February 10, 2022

Actuarial outsourcing trends in the insurance industry

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

Deloitte Capital H Blog, February 10, 2022

By Tony Johnson, Maria Itteilag, and Ashlyn Johnson

As insurance industry leaders seek to transform the cost structures, capacity, and capabilities of their companies in response to business, regulatory, and technological challenges, the actuarial function is a natural focus for their attention. The actuarial function is a driver of growth and profitability of insurers, so maximizing its value generation is a tantalizing prospect. At the same time, the function is an expensive one, so a successful transformation can generate significant savings on the cost side by focusing the actuaries’ attention on value-creating activities as opposed to those better suited for other professionals and functions to own.

The promise of getting more for less from the actuarial function is tempered by challenges and risks inherent to transformation initiatives. According to Gartner, 70% of transformation initiatives in finance fail to deliver their expected benefits and our observations suggest that actuarial transformations are no exception.1

However, we also find savvy insurers who are bucking the odds of transformation failure. They are using outsourcing arrangements in the execution of actuarial transformations to bolster implementation success, and as an integral element in the design of a revamped actuarial function that can deliver greater value to insurers at a lower cost. Your company can potentially do the same.

The imperatives of actuarial transformation

Like any business transformation, successful actuarial transformation hinges on the ability to navigate two imperatives: the first imperative is design—the vision of what the function will become, and the second imperative is execution—the journey that must be undertaken to make the vision a reality. Transformation failures are usually rooted in the inability to meet one or both imperatives.

The involvement of actuaries in the design of the transformed function is necessary. After all, who knows the processes better than the people who use them every day? But necessary is not always sufficient. Actuaries are experts in their work, but you should not expect them to be familiar with the transformational potential of new technologies or new ways of structuring workflow and executing tasks. Without a fully informed view of the art of the possible, the new design of the function will not likely reach its full potential.

Moreover, executing functional transformations requires mustering the resources and skillsets needed to implement the transformation while conducting business as usual. In the actuarial function, this often entails using highly specialized and highly paid actuaries to design and implement the transformation. In some cases, the actuaries do not possess the skills needed for this work. In many more cases, they simply do not have the time. As insurance companies begin to transform, their actuaries become overloaded as they try to meet the ongoing dictates and priorities of daily business, as well as the dictates and priorities of the transformation efforts. Many transformations fail when people become overwhelmed while simultaneously performing the work of today and building the capabilities of tomorrow. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

1:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, cost-cutting, human resources, innovation, outsourcing, transformation

Monday, December 13, 2021

Better management through anthropology

strategy+business, December 13, 2021

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Kilito Chan

The next time you hear someone arguing that a liberal arts education is wasted on businesspeople, direct them to Gillian Tett’s Anthro-Vision. In this new book, the award-winning journalist, chair of the Financial Times’s US editorial board, and Cambridge Ph.D. in social anthropology makes a compelling, readable argument for the business value of her academic discipline. Tett finds that this value is delivered in three ways: anthropology makes the strange familiar, it makes the familiar strange, and it attunes awareness when listening for social silence.

“Making the strange familiar”—the quest to understand other people and cultures—goes back to the origins of the science of anthropology in the 19th century (although its main purpose in the early days was to justify “civilized” Western colonialists who were stealing the labor and resources of “primitive” peoples). In 1990, this quest—understanding, not plunder—led Tett to a remote village in Soviet Tajikistan, where she studied marriage rites for her Ph.D.

Making the strange familiar has also led marketers in a global economy to embrace anthropology in their quest to figure out how to sell their products to customers in far-flung markets. The resulting insights can be valuable indeed. Switzerland-based Nestlé’s sales of Kit Kat bars were lukewarm in Japan, until 2001, when marketing executives noticed that sales of the confection surged in December, January, and February on the island of Kyushu. Curious, they discovered that students associated the name Kit Kat with kitto katsu, which means “you must overcome” in the local dialect. The students were buying the bars for luck when they took their exams for high school and university. Nestlé built its Japanese marketing strategy around this insight, and by 2014, Kit Kat was the country’s best-selling confection. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:35 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, corporate success, innovation, strategy+business

Wednesday, December 8, 2021

Break Out to Open Innovation

Image courtesy of Daniel Garcia/theispot.com

Mercedes-Benz AG produces over 2 million passenger cars annually for a global market in the throes of transformation. Automakers are meeting new demands for electrification and connectivity, new competitors are arising, and customers have new expectations, such as the desire for sustainable mobility. All of these trends are driving the need to speed innovation in every facet of the automotive industry.

In 2016, R&D and digital business managers at Mercedes’s headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany, realized that their efforts to collaborate with startups — a valuable source of external innovation — were being hampered by the company’s existing innovation processes. Those processes were overly focused on internal development and ready-to-implement solutions provided by the company’s established base of suppliers and weren’t well suited to uncertainty-ridden collaborations with promising technology startups. The company needed an innovation pathway capable of more effectively integrating startups earlier in the R&D process and significantly reducing the time required to identify, develop, test, and implement their most promising technologies and solutions.

In response, a new team within R&D was formed to build a better bridge between the promising ideas of external startups and the innovation needs of Mercedes’s internal business units. The team joined forces with partners from academia and industry to cofound Startup Autobahn, what we call an open corporate accelerator (CA). Unlike a conventional corporate accelerator — typically established by a single company for its own benefit — an open CA welcomes multiple sponsor companies and can attract a broader array of more mature startups. This model, also known as a consortium accelerator, improves sponsor access to external innovation and enhances the overall competitiveness of regional ecosystems...read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:38 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, entrepreneurship, innovation, partnering, platforms

Friday, October 16, 2020

Uncertainty on the menu

strategy+business, October 16, 2020

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Yagi Studio

If you’re a foodie, the research that Vaughn Tan undertook to write The Uncertainty Mindset will strike you as a dream gig. The assistant professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at University College London’s School of Management spent much of the past decade studying — and embedded within — the culinary R&D teams associated with a handful of the world’s top purveyors of high-end cuisine, including José Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup, Nathan Myhrvold’s Modernist Cuisine, Heston Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck, René Redzepi’s Noma, and “Amaja” (a pseudonym Tan uses for a restaurant that sounds a lot like Poul Andrias Ziska’s Koks). Aside from the good eats, Tan came away from his research with unconventional ideas for structuring and stimulating innovation teams.

The innovation challenge facing these rarefied culinary organizations is daunting; the customer expectations of an Apple or a Tesla pale by comparison. Imagine trying to satisfy a discerning gourmand who has waited a year for a reservation and then traveled from Singapore to the Faroe Islands solely for an 18-course meal. It is expected to be one of the best meals in the world. Each course features unusual ingredients prepared in unique ways that not only engage the senses but also impart the identity of the chef and the restaurant, so much so that it couldn’t have come from any other kitchen. Tan calls this elusive quality familiar novelty. “Novelty combined with distinctive familiarity makes for loyal customers — and is nearly impossible to copy,” he writes.

Outside London, at The Fat Duck Experimental Kitchen (FDEK), Tan observes pastry chef Isabel Rodriguez as she creates a dessert that will anchor an entirely new menu. “The team had decided that it would have to convey the feeling, as Rodriguez said, of being ‘dreamy, comforting, surreal. Like how you feel when you are about to fall asleep when you’re small. You’ve been bathed, and you’re feeling clean and tired, and everything smells like baby powder,’” writes Tan. Before the work is done, the dish, which the team calls Counting Sheep, will evolve into two dishes served in quick succession. Among its many fine details is the design and fabrication of a spoon with a fuzzy handle that will be dusted lightly with, yes, baby powder.

At Amaja, the R&D team spends three months figuring out how to cook 200-year-old mahogany clams — an ingredient never before used in high cuisine. In ThinkFoodGroup’s first Las Vegas venture, the company takes on the high-pressure work of launching three restaurants — serving tapas, Chinese–Mexican food, and a tasting menu — on the opening night of a newly constructed gaming resort.

In observing how culinary R&D team members work individually and together on such projects, Tan uncovers six “innovation insights” that serve as the core findings of his book. Two of the insights are particularly intriguing. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:20 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, creativity, innovation, org culture, strategy+business

Thursday, September 3, 2020

Competing on Customer Outcomes

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, September 2, 2020

by Marco Bertini and Oded Koenigsberg

Image courtesy of Richard Borge/theispot.com

In his 1969 book The Marketing Mode, Harvard Business School professor Theodore Levitt immortalized a gentleman named Leo McGivena, who reportedly said: “Last year 1 million quarter-inch drill bits were sold — not because people wanted quarter-inch drill bits but because they wanted quarter-inch holes.” A half-century later, this insight is as compelling as it ever was — customers still want to buy meaningful outcomes (a particular sensation, a tangible benefit, or some combination of the two), not products and services. What’s changing is companies’ ability to become more accountable for those outcomes by helping customers navigate three critical checkpoints: accessing the solution, consuming (that is, experiencing or using) it, and getting it to perform as expected or above expectation.

Even so, most companies do not stake their success on these checkpoints. Instead, they sell quarter-inch drills and promise customers that the quarter-inch holes they desire will follow. Indeed, a revenue model focused on transferring the ownership of a product or service to the buyer may appear prudent because revenue accrues up front, and any risk associated with access, consumption, and performance is passed on to customers. But in reality it places an unnecessary burden on customers and ultimately shrinks the opportunity in the market. This contraction occurs when, for instance, customers are priced out or forgo a purchase because it is inconvenient, when they perceive ownership as too risky and decide not to buy, and when they resolve to pay less to account for the possibility that they will not make sufficient use of their purchase or that it will not perform as advertised.

Technological advances are enabling companies to rewrite the rules of commerce. Mobile communication, cloud computing, the internet of things, advanced analytics, and microtransactions offer sharper, more timely information that can illuminate when and how customers access and consume their products and services, and whether and how well those products and services perform. We call this information impact data — it enables companies to track and understand what happens to their solutions beyond the moment of purchase.

The way we see it, impact data — and the technologies that deliver and analyze it — is transforming corporate accountability for customer outcomes from a fashionable marketing slogan into a strategic imperative. Some organizations dismiss this imperative, hoping that it is another passing trend. Others (often intentionally) make their prices more ambiguous and thus less comparable across competitors, which impedes sound purchasing decisions on the customer side. These will not be winning plays in the long run. Instead, companies should start to embrace accountability for outcomes and change their revenue models accordingly before they are forced to do so by more enlightened competitors and disruptive startups.

In this article, we’ll describe three types of revenue models that can help companies win customers and drive growth in today’s increasingly transparent markets. The framework draws on insights from our respective academic areas of behavioral economics and operations, our research, and our ongoing interactions with companies. We’ll also provide guidance on developing and implementing the right revenue model for your company, unlocking the untapped market potential of your solutions, and capturing the lion’s share of the resulting value... Read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

11:10 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, customer experience, entrepreneurship, innovation, strategy

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

Driving Growth in Digital Ecosystems

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, August 18, 2020

by Ina M. Sebastian, Peter Weill, and Stephanie L. Woerner

High-growth companies don’t go it alone. Increasingly, they are achieving results by creating and orchestrating digitally connected ecosystems — coordinated networks of enterprises, devices, and customers — that create value for all of their participants.

Companies whose dominant business model is ecosystem driver — in both B2B and B2C domains, such as energy management, home ownership, and financial services — experienced revenue growth approximately 27 percentage points higher than the average for their industries, and had profit margins 20 percentage points above the average for their industries, according to our research. That 2019 global survey of 1,311 executives also found that successful drivers achieve outsized results by attracting the partners needed to provide complementary — and competing — products and services that make their ecosystems seamless “one-stop shopping” destinations for customers.

Complementary offerings make it easier for customers to obtain comprehensive solutions to their problems. For example, when China’s largest insurer, Ping An, realized that its customers wanted not only insurance but also a means of addressing their medical and well-being needs, it created Good Doctor. The Good Doctor platform offers 24-7 one-stop health care services that are provided by pharmacies, hospitals, and about 10,000 doctors. In September 2019, Good Doctor reported serving more than 62 million customers monthly. Moreover, nearly 37% of Ping An customers used more than one of its services in 2019 — an important measure of ecosystem success.

As all of this suggests, a strong partnering capability is required to successfully grow digital ecosystems. This capability must be designed to support digital partnering, which is not the same as the traditional handshake and bespoke partnering of the physical world. Traditional partnering often includes exclusive relationships, long-term contracts, and deep integrations, all of which take time to establish and require strategic commitment. Digital partnering creates growth by adding more products and customers via digital connections with other companies that enable fast response to customer needs. It requires the ability to determine and agree with partners about who will create value, how revenue will be apportioned, and what data will be shared; it also requires the capacity to quickly add partners’ products and services via plug-and-play connections that offer immediate order and payment processing, and sometimes delivery as well.Successful ecosystem drivers also offer their customers greater choice, even when that entails featuring competing offers. In Australia, real estate platform driver Domain partners with about 35 mortgage lenders to offer homebuyers more loan choices. In the second half of 2019, the company’s Consumer Solutions segment, which consists of its loans, insurance, and utilities connections businesses, grew revenue by 72%...read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:54 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, digitization, innovation, management, partnering, platforms, technology

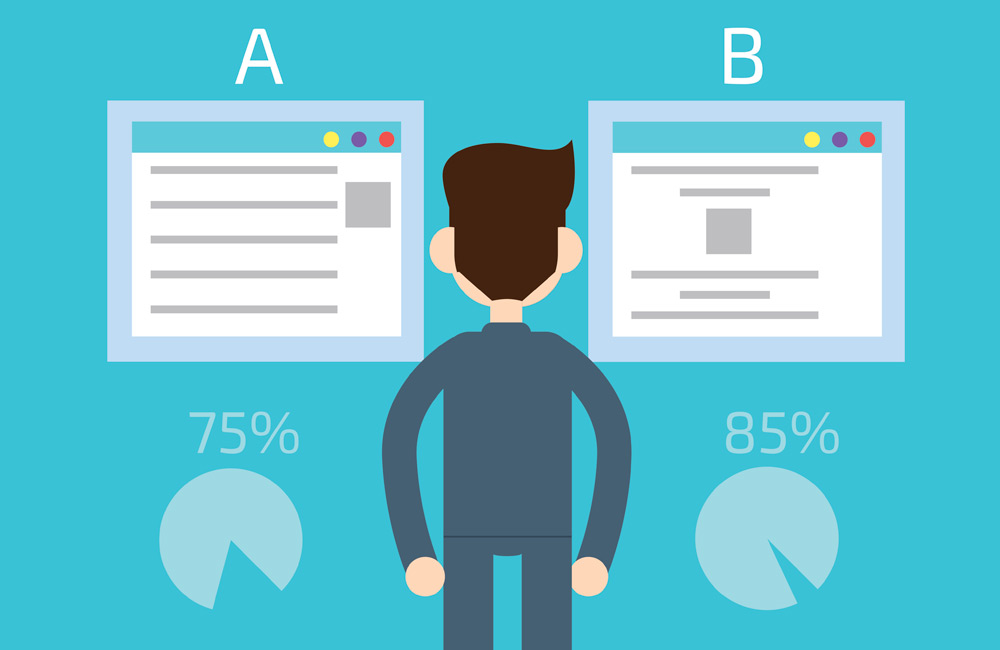

Thursday, June 4, 2020

Want to Make Better Decisions? Start Experimenting

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, Summer, 2020

by Michael Luca and Max H. Bazerman

Image courtesy of Ken Orvidas/theispot.com

Suppose you work on Google’s advertising team and need to decide whether ads should have a blue background or a yellow background. You think that yellow would attract the most clicks; your colleague thinks that blue is better. How do you make the decision?

In Google’s early days, the two of you might have debated the issue until someone caved or you both agreed to kick the decision up to the boss. But ultimately, it dawned on leaders throughout Google that many of these debates and decisions were unnecessary.

“We don’t want high-level executives discussing whether a blue background or a yellow background will lead to more ad clicks,” Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist, told us. “Why debate this point, since we can simply run an experiment to find out?”

Varian worked with the team that developed Google’s systematic approach to experimentation. The company now runs experiments at an extraordinary scale — more than 10,000 per year. The results of these experiments inform managerial decisions in a variety of contexts, ranging from advertising sales to search engine parameters.

More broadly, an experimental mindset has permeated much of the tech sector and is spreading beyond that. These days, most major tech companies, such as Amazon, Facebook, Uber, and Yelp, wouldn’t make an important change to its platforms without running experiments to understand how it might influence user behavior. Some traditional businesses, such as Campbell Soup Co., have been dipping their toes into experiments for decades. And many more are ramping up their efforts in experimentation as they undergo digital transformations. In a dramatic departure from its historic role as an esoteric tool for academic research, the randomized controlled experiment has gone mainstream. Startups, international conglomerates, and government agencies alike have a new tool to test ideas and understand the impact of the products and services they are providing. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

10:33 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: analytics, corporate success, data science, decision making, experiments, innovation, management

Tuesday, June 2, 2020

Making experiments pay

strategy+business, June 2, 2020

by Theodore Kinni

Illustration by AndSim

The current pandemic is a dramatic case study in why experiments matter. How else are we to know which tests accurately identify COVID-19 infections and their telltale antibodies, whether and how well drugs already at our disposal mitigate the suffering inflicted by the coronavirus, or whether the vaccines currently in development will actually protect us from it? Randomized controlled trials are the only way to answer these questions short of playing Russian roulette with the lives of large numbers of people.

Experiments have been around for a long time. In The Power of Experiments, an introductory paean to the benefits of experimentation for corporate and government decision making, Harvard Business School professors Michael Luca and Max Bazerman peg the first recorded experiment to the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar in Babylonia circa 600 BC.

As the Old Testament story goes, Nebuchadnezzar attacked Jerusalem and took a group of young Israelites, including one named Daniel, as servants. He ordered that they be acculturated for three years, in part by being fed the same food as the royal court, which the Israelites considered “ritually unclean.” But Daniel proposed that he and three other prisoners be fed only vegetables and water for 10 days, at which point a guard would compare their health to that of the rest of the prisoners, who would have been fed the local fare. At the end of the experiment, the guard judged the vegetarians healthier, and Daniel and his three comrades were able to continue eating the less objectionable diet.

About 2,600 years later, Luca and Bazerman write, “We are in the early days of the age of experiments.” By this, they mean that experiments have spread far beyond the boundaries of science labs and medical trials. In 2018, Google ran more than 10,000 experiments. Amazon, Facebook, Uber, Yelp, and TripAdvisor run thousands of experiments per year. As these names indicate, technology companies, especially those with digital platforms, are at the forefront of corporate experimentation. That’s because it is relatively easy to run experiments on their large, captive audiences. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

10:22 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, corporate success, data science, decision making, experiments, innovation, strategy+business, technology

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

The Future of Platforms

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, February 11, 2020

by Michael A. Cusumano, David B. Yoffie, and Annabelle Gawer

The world’s most valuable public companies and its first trillion-dollar businesses are built on digital platforms that bring together two or more market actors and grow through network effects. The top-ranked companies by market capitalization are Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google’s parent company), and Amazon. Facebook, Alibaba, and Tencent are not far behind. As of January 2020, these seven companies represented more than $6.3 trillion in market value, and all of them are platform businesses.

Platforms are also remarkably popular among entrepreneurs and investors in private ventures. When we examined a 2017 list of more than 200 unicorns (startups with valuations of $1 billion or more), we estimated that 60% to 70% were platform businesses. At the time, these included companies such as Ant Financial (an affiliate of Alibaba), Uber, Didi Chuxing, Xiaomi, and Airbnb.

Platforms are also remarkably popular among entrepreneurs and investors in private ventures. When we examined a 2017 list of more than 200 unicorns (startups with valuations of $1 billion or more), we estimated that 60% to 70% were platform businesses. At the time, these included companies such as Ant Financial (an affiliate of Alibaba), Uber, Didi Chuxing, Xiaomi, and Airbnb.But the path to success for a platform venture is by no means easy or guaranteed, nor is it completely different from that of companies with more-conventional business models. Why? Because, like all companies, platforms must ultimately perform better than their competitors. In addition, to survive long-term, platforms must also be politically and socially viable, or they risk being crushed by government regulation or social opposition, as well as potentially massive debt obligations. These observations are common sense, but amid all the hype over digital platforms — a phenomenon we sometimes call platformania — common sense hasn’t always been so common.

We have been studying and working with platform businesses for more than 30 years. In 2015, we undertook a new round of research aimed at analyzing the evolution of platforms and their long-term performance versus that of conventional businesses. Our research confirmed that successful platforms yield a powerful competitive advantage with financial results to match. It also revealed that the nature of platforms is changing, as are the ecosystems and technologies that drive them, and the challenges and rules associated with managing a platform business.

Platforms are here to stay, but to build a successful, sustainable company around them, executives, entrepreneurs, and investors need to know the different types of platforms and their business models. They need to understand why some platforms generate sales growth and profits relatively easily, while others lose extraordinary sums of money. They need to anticipate the trends that will determine platform success versus failure in the coming years and the technologies that will spawn tomorrow’s disruptive platform battlegrounds. We seek to address these needs in this article. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

3:34 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: artificial intelligence, books, corporate success, digitization, innovation, platforms, strategy, technology

Friday, June 14, 2019

Conversational computing

strategy+business, June 13, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

by Theodore KinniSteve Jobs could be relentless when he wanted something. In early 2010, he wanted a small startup in San Jose, Calif. CEO Dag Kittlaus and his cofounders had just raised a second round of funding and didn’t want to sell. Jobs called Kittlaus for 37 days straight, until he wrangled and wheedled a deal to buy the two-year-old venture for Apple at a price reportedly between US$150 million and $200 million. The company was Siri Inc.

Wired contributor James Vlahos tells the story of how Siri took up permanent residence in the iPhone in his new book, Talk to Me. It’s the first nontechnical book on voice computing that I’ve seen and a must-read if you have any interest in the topic.

Vlahos spends the first third of Talk to Me describing the platform war currently raging in voice computing. It details the race among the big players, including Amazon, Google, and Apple, to embed AI-driven voices in as many different devices as possible, as they seek to dominate the emerging ecosystem. The fact that Amazon now has more than 10,000 employees working on Alexa provides a good sense of the dimensions of that race.

But voice computing is more than a platform play. It is likely to have ramifications and applications for every company, especially if Vlahos’s contention that “the advent of voice computing is a watershed moment in human history” turns out to be right.

“Voice is becoming the universal remote to reality, a means to control any and every piece of technology,” he writes. “Voice allows us to command an army of digital helpers — administrative assistants, concierges, housekeepers, butlers, advisors, babysitters, librarians, and entertainers.” Voice will disrupt the business models of powerful companies — and create new opportunities for upstarts — in part because it will put AI directly in the control of consumers, Vlahos argues. “And voice introduces the world to relationships long prophesied by science fiction — ones in which personified AIs become our helpers, watchdogs, oracles, and friends.” Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:56 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: AI, bizbook review, books, corporate success, digitization, innovation, strategy+business, technology, voice computing

Transformation in energy, utilities and resources

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

PwC, June 13, 2019

The world is at the midpoint of a massive energy-related transformation. By 2040, the global demand for all forms of fuel and power will be four times what it was in 1990. During the same 50 years, the issue of global climate change will have moved from the margins to the centre. Institutions everywhere will be striving to address climate-related problems by dramatically decreasing and mitigating carbon use.

In the energy, utilities and resources (EU&R) industries, the relationship between these two dynamics — the rise in demand and the recognition of carbon use as a climate threat — is already determining basic strategic choices. And it will continue to do so for years to come. This development will profoundly affect a wide range of companies: producers of all forms of energy; disseminators and sellers of electric power, gas and oil; energybased process industries such as chemicals and steel; and producers of other extracted commodities. Leaders in all those businesses will need the acumen to make and execute decisions that combine growth with environmental sustainability, often in novel ways.

The ability to take this new approach to management, especially for companies that have been successful in the past, is not guaranteed. Thus, transformation — the ability to make fundamental shifts in strategy, operating model and day-to-day activity — is on the agenda for EU&R companies this year, with a stronger sense of urgency than before. Fortunately, because of the rise of digital technology, the growing use of interoperable platforms and an emerging consensus about the value of renewable energy, EU&R companies have more tools and opportunities than ever before for thriving through this disruption.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

6:16 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: competitive intelligence, corporate success, EU&R, innovation, leadership, transformation

Tuesday, June 11, 2019

Using AI to Enhance Business Operations

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, June 11, 2019

by Monideepa Tarafdar, Cynthia M. Beath, and Jeanne W. Ross

Artificial intelligence invariably conjures up visions of self-driving vehicles, obliging personal assistants, and intelligent robots. But AI’s effect on how companies operate is no less transformational than its impact on such products.

Enterprise cognitive computing — the use of AI to enhance business operations — involves embedding algorithms into applications that support organizational processes. ECC applications can automate repetitive, formulaic tasks and, in doing so, deliver orders-of-magnitude improvements in the speed of information analysis and in the reliability and accuracy of outputs. For example, ECC call center applications can answer customer calls within 5 seconds on a 24-7-365 basis, accurately address their issues on the first call 90% of the time, and transfer complex issues to employees, with less than half of the customers knowing that they are interacting with a machine. The power of ECC applications stems from their ability to reduce search time and process more data to inform decisions. That’s how they enhance productivity and free employees to perform higher-level work — specifically, work that requires human adaptability and creativity. Ultimately, ECC applications can enhance operational excellence, customer satisfaction, and employee experience.

ECC applications come in many flavors. For instance, in addition to call center applications, they include banking applications for processing loan requests and identifying potential fraud, legal applications for identifying relevant case precedents, investment applications for developing buy/sell predictions and recommendations, manufacturing applications for scheduling equipment maintenance, and pharmaceutical R&D applications for predicting the success of drugs under development.

Not surprisingly, most business and technology leaders are optimistic about ECC’s value-creating potential. In a 2017 survey of 3,000 senior executives across industries, company sizes, and countries, 63% said that ECC applications would have a large effect on their organization’s offerings within five years. However, the actual rate of adoption is low, and benefits have proved elusive for most organizations. In 2017, when we conducted our own survey of senior executives at 106 companies, half of the respondents reported that their company had no ECC applications in place. Moreover, only half of the respondents whose companies had applications believed they had produced measurable business outcomes. Other studies report similar results.

This suggests that generating value from ECC applications is not easy — and that reality has caught many business leaders off guard. Indeed, we found that some of the excitement around ECC resulted from unrealistic expectations about the powers of “intelligent machines.” In addition, we observed that many companies that hoped to benefit from ECC but failed to do so had not developed the necessary organizational capabilities. To help address that problem, we undertook a program of research aimed at identifying the foundations of ECC competence. We found five capabilities and four practices that companies need to splice the ECC gene into their organization’s DNA. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:21 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: AI, analytics, corporate success, innovation, management, work

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Large businesses don’t have to be lousy innovators

strategy+business, April 11, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Kanchisa Thitisukthanapong

Gary Pisano, author of Creative Construction: The DNA of Sustained Innovation, doesn’t buy the idea that large enterprises are inherently lousy innovators. Back in 2006, Pisano, the Harry E. Figgie Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, traced the origin of every drug approved by the FDA over a 20-year period to either one of the world’s 20 largest pharmaceutical companies or one of the 250 smaller, supposedly more innovative biotechs. When he compared the two groups, he discovered a “statistical dead heat” — R&D productivity was no better in the smaller biotechs than in big pharma.

Pisano also points to anecdotal evidence to support his opposition to the conventional wisdom about innovation in large enterprises. For every big, established company that failed at transformational innovation (think Blockbuster, Kodak, and Polaroid), he points to another that has succeeded. In 1964, when IBM announced its revolutionary 360 mainframe computers, it was already the largest computer company in the world and ranked 18th on the Fortune 500. In 1982, when Monsanto scientists invented the foundational technology for GMOs (genetically modified organisms), the company was 81 years old and number 50 on the Fortune 500. And in 2007, when Apple launched the iPhone, it had sales of US$24 billion and already stood at 123rd on the Fortune 500.

Pisano says that the difference between a Blockbuster and an IBM is the ability of leaders to sustain and rejuvenate the innovation capacity of their companies. It’s an ability he calls “creative construction,” and he writes that it “requires a delicate balance of exploiting existing resources and capabilities without becoming imprisoned by them.”

Walking that tightrope is a challenge for large companies. It’s tough to move the needle with innovation when the needle’s scale is measured in billions of dollars. “For J&J [Johnson & Johnson] to maintain its historical rate of top-line growth,” reports Pisano, “it must generate about $3 billion–$4 billion of new revenue per year.” The complexity of managing innovation in large organizations can also be daunting. “When you get to be the scale of a J&J, you have a lot of moving parts,” he explains. “You now have a system with serious frictions. Friction impedes mobility. Lack of mobility means lack of innovation.”

But large companies also have some advantages that can give them a leg up in innovation. “Larger enterprises like J&J have massive financial resources to explore new opportunities,” says Pisano. They can hedge their bets, tap deep reservoirs of talent, navigate regulatory agencies, and use their huge distribution networks and strong brands to roll out new products to millions of existing customers. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:53 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, corporate success, creativity, innovation, leadership, org culture, strategy+business

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Leadership lessons from a guitar hero

strategy+business, March 19, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

About an hour into Still on the Run, a documentary exploring the career of rock guitar god Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, another deity in the pantheon, pops up on screen and says, “I don’t even know how he’s doing it half the time.” Clapton is talking about Beck’s ability to give voice to the guitar. But his comment set me to wondering how Beck developed his unique style and what, if any, lessons his nearly 60-year career might offer those who aspire to reach the top of the business world.

With CEO tenure in large companies running five years or so, the fact that Beck has been numbered among the world’s best guitarists for about 10 times that long is worth exploring. Surely, innate talent and endless hours of practice count for a lot. But loads of guitarists have both, and haven’t had careers that lasted as long as the average CEO’s. Beck, however, has been an inveterate seeker of innovation in both technology and technique. And this habit has enabled the 74-year-old London-born musician to continuously expand his capabilities and transform his sound.

Jeff Beck performs at the Bataclan in Paris in 1973.

Photograph by Philippe Gras / Alamy

As biographer Martin Power tells it in Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck (Omnibus Press, 2014), Beck’s parents valued musicianship, but not the electric guitar, which in the 1950s was associated with rockabilly and other disreputable musical genres. When his parents refused even to spring for new strings for a borrowed guitar, the teenager began building his own crude instruments. Unable to tune his early efforts, Beck learned to bend the strings to pitch while playing, a work-around that became a signature. The wannabe lead guitarist stole the pickup needed for his first electric guitar and built its amp in his school’s science department. Since then, Beck continually explored and adopted technological advances in guitar effects and electronics — such as tape-delay units, fuzz boxes, and guitar synthesizers — to shape and extend his playing.

Beck’s eagerness to learn and incorporate techniques from far-flung places is another hallmark of his career. Like Clapton, he learned from American blues giants — and rode the wave of cultural appropriation that gave rise to rock and roll. According to Power’s biography, Beck says that the first time he heard Jimi Hendrix play, he thought, “Oh, Christ, all right, I’ll become a postman.” Then he followed Hendrix around to learn how he created his sound. Other inspirations include a women’s choir that recorded Bulgarian folk songs, operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti, and electronic dance music. Beck describes his resulting style as “a form of insanity…. A bit of everything, really. Rockabilly licks, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, all the people I’ve loved to listen to over the years. Cliff [Gallup], Les [Paul], Eastern and Arabic music, it’s all in there.” Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:12 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: creativity, innovation, leadership, personal success, strategy+business, work