Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

Boston Consulting Group, March 11, 2022

by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Balázs Zoletnik

From media and technology to energy and mining—no major industry is untouched by the rise of business ecosystems. These dynamic groups of largely independent economic players working together to deliver solutions that they couldn’t muster on their own come in two flavors: transaction ecosystems in which a central platform links two sides of a market, such as buyers and sellers on a digital marketplace; and solution ecosystems in which a core firm orchestrates the offerings of several complementors, such as product manufacturers in a smart-home ecosystem. Both types can quickly generate eye-popping valuations; since 2015, more than 300 ecosystem startups have reached unicorn status.

Given the success of this cohort of startups, as well as the Big Tech ecosystem players now numbered among the world’s most valuable companies, it’s no surprise that ecosystems are high on the strategic agendas of incumbent companies. More than half of the S&P Global 100 companies are already engaged in one or more ecosystems, and in a recent BCG survey of 206 executives in multinational companies, 90% indicated that their companies planned to expand their activities in this field.

Yet many leaders of incumbent companies are still unsure how to define their ecosystem strategies. This article aims to help them in that pursuit. It is informed by the insights we’ve gleaned from three years of ecosystem research and engagements with large enterprises across industries and geographies. Organized in eight fundamental questions, it offers a step-by-step framework for developing a company’s ecosystem strategy. Read the rest here.

Monday, March 14, 2022

What Is Your Business Ecosystem Strategy?

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

2:07 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: business ecosystems, corporate success, digitization, platforms, strategy

Tuesday, November 23, 2021

Setting the Rules of the Road

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand on this article:

MIT Sloan Management Review, November 22, 2021

by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Niklas Knust

Image courtesy of Cathy Gendron/theispot.com

The rapid rise of a few powerful digital ecosystems disguises a harsh reality about this business model: Less than 15% of business ecosystems are sustainable in the long run. When we examined 110 failed ecosystems in a variety of industries, we found that more than a third of the failures stemmed from their governance models — that is, the explicit and/or implicit structures, rules, and practices that frame and direct the behavior and interplay of ecosystem participants.

Business ecosystems are prone to different types of governance failures. One reason why the BlackBerry OS lost its competition with Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android was because Research In Motion failed to open its app ecosystem widely to developers until it was too late. Conversely, the video game industry fell into recession during the so-called Atari Shock in the 1980s in part because of overly open access to its ecosystem, which resulted in a flood of inferior games. Badly behaved platform participants, conflicts among ecosystem partners, and backlash from consumers or regulators are other indicators of governance flaws that can bring down an ecosystem.

Many orchestrators struggle to find an effective governance model because managing an ecosystem is very different from managing an integrated company or a linear supply chain. Ecosystems rely on voluntary collaboration among independent partners rather than clearly defined customer-supplier relationships and transactional contracts. The orchestrator cannot exert hierarchical control but must convince partners to join and collaborate in the ecosystem. These challenges are exacerbated by the dynamic nature of many ecosystems, which develop and evolve quickly and continually add new products, services, and members.

Ecosystem leaders who understand the components of a comprehensive governance model and glean insights from ecosystem successes and failures can make more informed and explicit governance decisions. In doing so, they can improve the odds that their ecosystems will be among the lucky few that survive and prosper over the long term. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

1:33 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: business ecosystems, corporate success, platforms

Monday, March 29, 2021

The Overlooked Partners That Can Build Your Talent Pipeline

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, March 29, 2021

by Nichola J. Lowe

Image courtesy of Stephanie Dalton Cowan/theispot.com

America has a skill problem. It’s not the result of inadequate educational systems letting down younger workers or a lack of aptitude among older workers, as some claim. The problem is the widespread failure of American companies to share responsibility for skill development. Many employers are simply unwilling — or unable — to invest sufficient resources, time, and energy into work-based learning and the creation of skill-rewarding career pathways that extend economic opportunity to workers on the lowest rungs of the labor market ladder.

This national skills crisis becomes clearest whenever unemployment rates are low. As late as February 2020, most industries in the U.S. showed persistent signs of skills shortages. In manufacturing, for instance, there were 522,000 unfilled job openings in late 2019. There were similar long-standing job vacancies in many other critical industries, including financial and business services, health care, and telecommunications, with executives noting increased skills gaps in data analytics, information technology, and web design, among other areas.

The skills shortage was less obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, as companies shed millions of jobs, but it persists despite that temporary softening of the labor market. And as hiring picks up along with the economy, employers may increasingly develop workforce strategies that are based not only on skills requirements but on increased commitments to boosting diversity and inclusion.

A better and more enduring skills strategy must begin with the recognition that our national skills crisis rests on a deeply rooted but flawed assumption: namely, that skills are individually held. This view overlooks the collective and context-specific nature of skills — that is, the ways in which they are shared, reinforced, and reproduced through group interactions at work. It also creates a false justification for the bias and hoarding that often accompany employers’ approaches to talent management. That results in more educated workers benefiting from corporate investments in retention, leaving those workers with less formal education underserved and undervalued — a phenomenon that labor scholars call the “great training paradox.” Moreover, it leads to the mistaken categorization of entry-level workers as “unskilled.” This positions them as irrelevant and easy to replace, ignoring the fact that this segment of the workforce — so often women and people of color —not only executes strategy but also has the grounded insights needed to improve organizational processes and practices.

The core assumption that skill is individually held results in supply-side approaches that place the primary burden for skill development on educational institutions and on students within them. These approaches have not and cannot, in isolation, do the trick. Skill shortages are a problem of employment, not education...read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:53 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: book adaptation, books, business ecosystems, corporate success, education, government, human resources, nonprofits, partnering, work

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

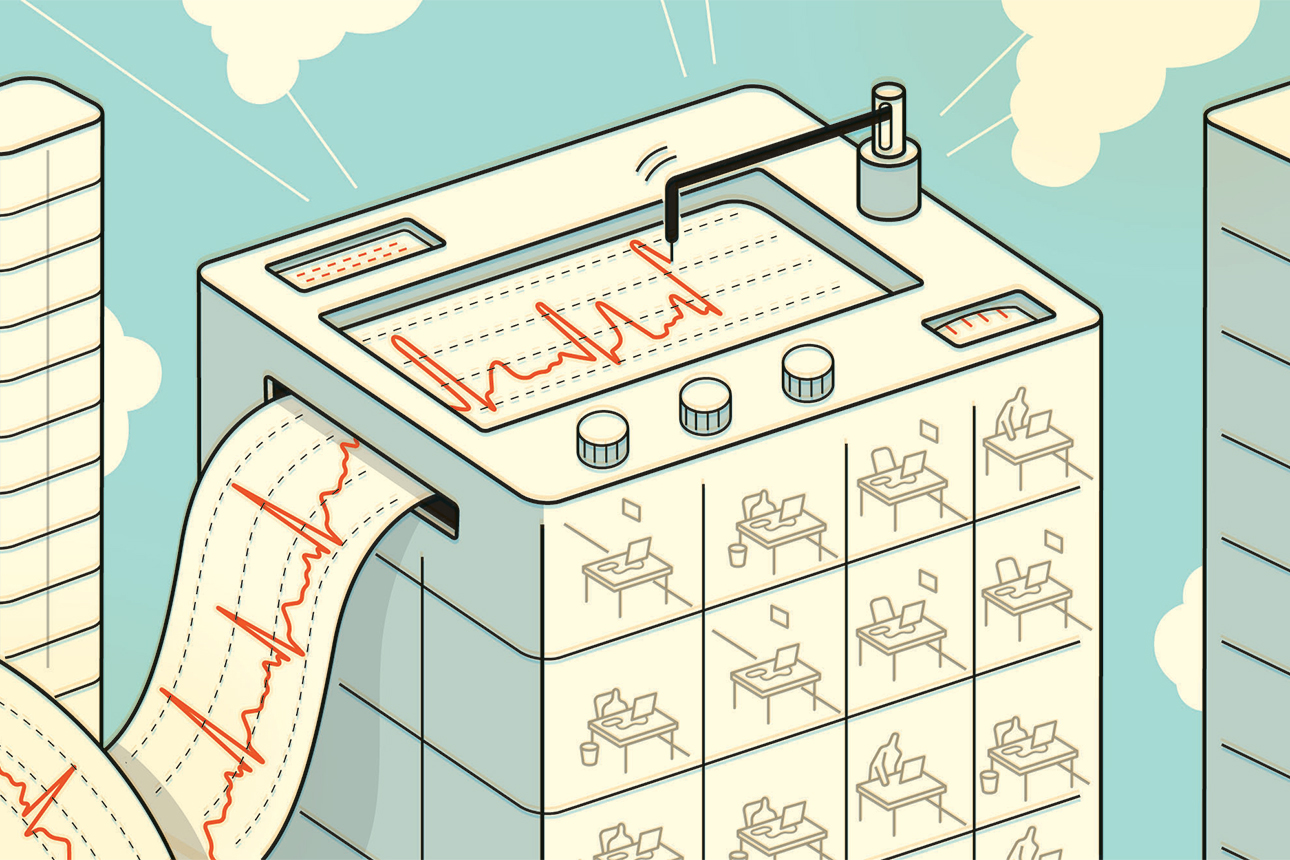

How Healthy Is Your Business Ecosystem?

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, March 9, 2021

by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Edzard Wesselink

Image courtesy of Harry Campbell/theispot.com

Companies that start or join successful business ecosystems — dynamic groups of largely independent economic players that work together to create and deliver coherent solutions to customers — can reap tremendous benefits. In the startup phase, ecosystems can provide fast access to external capabilities that may be too expensive or time-consuming to build within a single company. Once launched, ecosystems can scale quickly because their modular structure makes it easy to add partners. Moreover, ecosystems are very flexible and resilient — the model enables high variety, as well as a high capacity to evolve. There is, however, a hidden and inconvenient truth about business ecosystems: Our past research found that less than 15% are sustainable in the long run.

The seeds of ecosystem failure are planted early. Our new analysis of more than 100 failed ecosystems found that strategic blunders in their design accounted for 6 out of 7 failures. But we also found that it can take years before these design failures become apparent — with all the cumulative investment losses in time, effort, and money that failure implies.

Witness Google, which made several unsuccessful attempts to establish social networks. It invested eight years in Google+ before shutting down the service in 2019. One reason for the Google+ failure was its asymmetric follow model, similar to Twitter’s, in which users can unilaterally follow others. This created strong initial growth but did not build relationships, which might have fostered greater engagement on the platform. The downfall of another Google social network, Orkut, was built into its unusually open design, which let users know when their profiles were accessed by others. It turned out that users were uncomfortable with this lack of privacy, and the network went offline in 2014, 10 years after its launch.

Typically, ecosystems are assessed using two kinds of metrics: conventional financial metrics, such as revenue, cash burn rate, profitability, and return on investment; and vanity metrics, such as market size and ecosystem activity (number of subscribers, clicks, or social media mentions). The former are not very useful for assessing the prospects of ecosystems because they are backward-looking. The latter can be misleading because they are not necessarily linked to value creation or extraction. They indicate the current interest in the ecosystem, and presumably its potential, but may also reflect an ecosystem’s ability to spend investors’ money on marketing and other growth tactics more than its ability to generate value.

To improve the odds of success and mitigate the high costs of failure, leaders must be able to assess the health of a business ecosystem throughout its life cycle. They need metrics that indicate performance and potential at the system level and at the level of the individual companies or partners participating in the ecosystem, as well as the ecosystem leader or orchestrator. They need to be able to gauge growth in terms of scale not only in ecosystem participation but also in the underlying operating model. And most critically, they need metrics that reflect the success factors unique to each of the distinct phases of ecosystem development.

This article lays out a set of metrics and early warning indicators that can help you determine whether your ecosystem is on track for success and worthy of continued investment in each development phase. They can also help you identify emerging issues and decide if and when you may need to cut your losses in an ecosystem and/or reorient it. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: business ecosystems, corporate success, economic systems, management, platforms, strategy