Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, March 9, 2021

by Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Edzard Wesselink

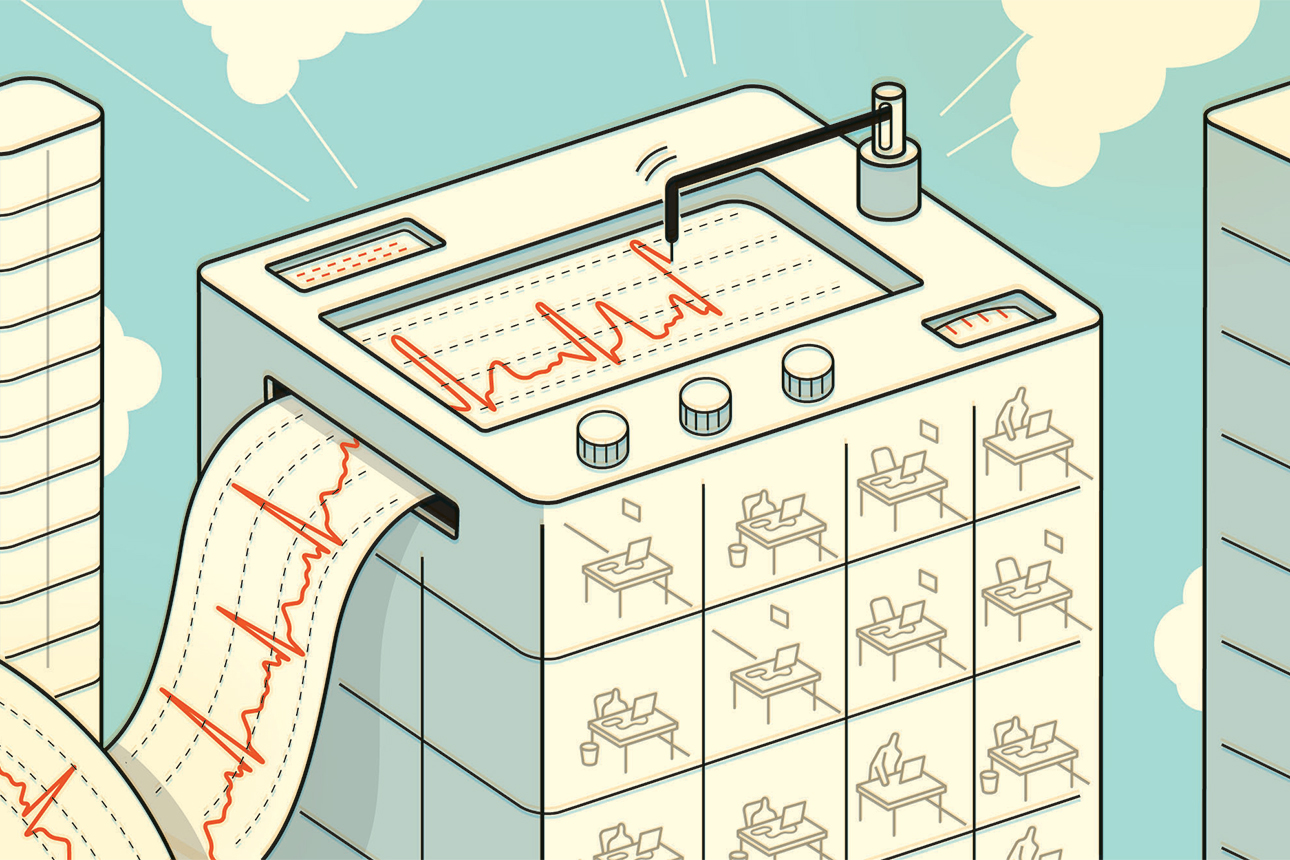

Image courtesy of Harry Campbell/theispot.com

Companies that start or join successful business ecosystems — dynamic groups of largely independent economic players that work together to create and deliver coherent solutions to customers — can reap tremendous benefits. In the startup phase, ecosystems can provide fast access to external capabilities that may be too expensive or time-consuming to build within a single company. Once launched, ecosystems can scale quickly because their modular structure makes it easy to add partners. Moreover, ecosystems are very flexible and resilient — the model enables high variety, as well as a high capacity to evolve. There is, however, a hidden and inconvenient truth about business ecosystems: Our past research found that less than 15% are sustainable in the long run.

The seeds of ecosystem failure are planted early. Our new analysis of more than 100 failed ecosystems found that strategic blunders in their design accounted for 6 out of 7 failures. But we also found that it can take years before these design failures become apparent — with all the cumulative investment losses in time, effort, and money that failure implies.

Witness Google, which made several unsuccessful attempts to establish social networks. It invested eight years in Google+ before shutting down the service in 2019. One reason for the Google+ failure was its asymmetric follow model, similar to Twitter’s, in which users can unilaterally follow others. This created strong initial growth but did not build relationships, which might have fostered greater engagement on the platform. The downfall of another Google social network, Orkut, was built into its unusually open design, which let users know when their profiles were accessed by others. It turned out that users were uncomfortable with this lack of privacy, and the network went offline in 2014, 10 years after its launch.

Typically, ecosystems are assessed using two kinds of metrics: conventional financial metrics, such as revenue, cash burn rate, profitability, and return on investment; and vanity metrics, such as market size and ecosystem activity (number of subscribers, clicks, or social media mentions). The former are not very useful for assessing the prospects of ecosystems because they are backward-looking. The latter can be misleading because they are not necessarily linked to value creation or extraction. They indicate the current interest in the ecosystem, and presumably its potential, but may also reflect an ecosystem’s ability to spend investors’ money on marketing and other growth tactics more than its ability to generate value.

To improve the odds of success and mitigate the high costs of failure, leaders must be able to assess the health of a business ecosystem throughout its life cycle. They need metrics that indicate performance and potential at the system level and at the level of the individual companies or partners participating in the ecosystem, as well as the ecosystem leader or orchestrator. They need to be able to gauge growth in terms of scale not only in ecosystem participation but also in the underlying operating model. And most critically, they need metrics that reflect the success factors unique to each of the distinct phases of ecosystem development.

This article lays out a set of metrics and early warning indicators that can help you determine whether your ecosystem is on track for success and worthy of continued investment in each development phase. They can also help you identify emerging issues and decide if and when you may need to cut your losses in an ecosystem and/or reorient it. Read the rest here.

Tuesday, March 9, 2021

How Healthy Is Your Business Ecosystem?

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: business ecosystems, corporate success, economic systems, management, platforms, strategy

Sunday, February 9, 2020

Inside Mexico's Anemic Economy

LinkedIn, February 9, 2020

by Theodore Kinni

They say ignorance is bliss and it certainly used to feel that way whenever I ate a tortilla chip laden with guacamole. But now, because journalist Nathaniel Parish Flannery chose avocados, along with coffee and mezcal, as the principal entry points for his boots-on-the-ground exploration of the Mexican economy, Searching for Modern Mexico, I know a little too much about the main ingredient of guacamole to enjoy it’s creamy, green goodness as much as I once did.

Most of the avocados Americans consume come from Michoacán, a state located west of Mexico City that stretches to the Pacific Ocean. In 1995, the year after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed, Michoacán exported 45,600 tons of avocados. In 2015, it exported nearly 775,000 tons valued at $1.5 billion. But if this sounds like a free-trade success story, it’s not so much.

The wealth generated by avocados not only enriched Michoacán’s farmers, explains Flannery, but it also attracted criminals, many of them former members of drug cartels. These gangs of gunmen demanded 30-40 percent of the earnings of avocado producers as “protection money.” The gangs tortured and killed anyone who refused to pay, dumping the mutilated bodies in public squares as a warning.

The police and armed forces of Mexico’s local, state, and federal governments were unable to stop the killing, so the avocado growers of Michoacán formed and funded their own gangs, vigilantes called the autodefensa. A running battle ensued that continues today. Caravans of gunmen armed with automatic weapons speed through avocado country fighting for control. Gangs have splintered and reformed until it is impossible to tell the good guys from the bad guys. Cities and towns have been transformed into armed camps, with private armies manning turrets and barricades.

“The government doesn’t rule here, but it’s under control,” a grower in the city of Tancítaro tells Flannery. “You can relax.” Meanwhile, in the U.S., we are mashing avocados into guacamole as little as 30 hours after they were picked in Michoacán. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

3:25 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, economic systems, economics, entrepreneurship, globalization, government

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

All the healthcare you can afford

strategy+business, July 31, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

Illustration by adventtr

In 2014, a syllabus and sample lecture for a course entitled Introductory Korean Drama (pdf) surfaced at Princeton University. Written by the eminent healthcare economist Uwe Reinhardt, it began, “After the near‐collapse of the world’s financial system has shown that we economists really do not know how the world works, I am much too embarrassed to teach economics anymore, which I have done for many years. I will teach Modern Korean Drama instead.” It appears that some economics professors aren’t nearly as dismal as their science.

In the book, Reinhardt gets to the crux of the ongoing debate over the American healthcare system — in which solutions abound but relief is nowhere in sight — with just one question: “As a matter of national policy, and to the extent that a nation’s health system can make it possible, should the child of a poor American family have the same chance of avoiding preventable illness or of being cured from a given illness as does the child of a rich American family?”

“And so,” he laments, “permanently reluctant ever to debate openly the distributive social ethic that should guide our healthcare system, with many Americans thoroughly confused on the issue, we shall muddle through health reform, as we always have in the past, and as we always shall for decades to come.”

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

2:29 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, economic systems, economics, healthcare, strategy+business

Thursday, June 14, 2018

Lessons From China’s Digital Battleground

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, June 12, 2018

by Shu Li, François Candelon, and Martin Reeves

The explosive growth of the digital market in China, a country with more than 700 million internet users, constitutes a rich prize to companies that can exploit its opportunities. Five of the 10 largest public internet companies in the world — Tencent Holdings Ltd., Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., Baidu Inc., JD.com Inc. (aka Jingdong), and NetEase Inc. — have emerged from this $1 trillion market. And, by February 2018, Chinese companies accounted for 33% of the world’s unicorns (privately held startups valued at $1 billion or more), with almost three-quarters of them targeting digital or online markets.

Why have so many powerful Western players hit a wall in China? Protectionism is a convenient excuse, but we believe that it is an exaggerated one. Worse, it oversimplifies and obscures some important competitive realities in China that many Western players have missed.

Against this backdrop, China’s digital market developed in an exceptionally rapid and dynamic manner, one based on need rather than preference. Furthermore, the winning game plan for dominating digital markets turned out to have some unique characteristics with regards to localization, speed, online and offline integration, and local ecosystem development.

It is important for Western players to recognize and understand these characteristics. They are not only key to winning in China but also in other countries that share a similar profile, such as India and Indonesia. In addition, they provide valuable insight into how China’s digital giants may compete as they go global. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: business history, competitive intelligence, corporate success, economic systems, globalization, innovation, technology

Wednesday, February 28, 2018

A Better Way to Bring Science to Market

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, Feb. 28, 2018

by Joshua S. Gans

In 2012, when the Creative Destruction Lab (CDL) at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management was launched, the audacious target of this seed-stage program for massively scalable, science-based companies was $50 million in equity creation in five years. In 2017, CDL companies surpassed $790 million in equity creation. Such is the power of a market for judgment.

A market for judgment is a nexus between science and technology. By science, I mean the kind of knowledge that is produced in academic institutions and research labs. By technology, I mean the commercial application of that knowledge. A market for judgment is a place, like CDL, where the producers of knowledge meet and mingle with businesspeople and investors.

Markets for judgment are necessary and valuable because science and technology are mismatched in several ways. They are mismatched in geographic terms: Science is concentrated in universities, which are located all over the world; technology aggregates in a few places, such as California’s Silicon Valley and Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the U.S. The landscape of science is the gently undulating Great Plains whereas the landscape of technology spikes like Mount Olympus.

The distribution of scientific and technological talent is also mismatched. I think that may be because of the antithetical nature of the two jobs. Scientists are supposed to go down fruitless paths; it’s part of their process. Technologists are supposed to go down fruitful paths; in their process, fruitless paths are decidedly unwelcome and potentially destructive.

In short, although science and technology are supposed to go hand in hand, they usually can’t get that close. CDL was designed to determine if we could bring science and technology closer together by building a market for judgment. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

12:15 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, economic systems, education, entrepreneurship, innovation, technology

Wednesday, May 24, 2017

Cracking the Code of Economic Development

strategy+business, May 24, 2017

by Theodore Kinni

Philip E. Auerswald, associate professor at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government, calls this question “The Great Man–Machine Debate.” In his engaging and wide-ranging book, The Code Economy: A Forty-Thousand-Year History, he seeks to answer it by reframing how we think about economic dynamics and progress. “The microeconomics you learned in college was generally limited to the ‘what’ of production: what goes in and what comes out,” Auerswald writes. “This book is about the ‘how’: how inputs are combined to yield outputs.”

Auerswald has a more expansive definition of the word code than the typical computer scientist. For him, code encapsulates the how of production — that is, the technology and the instruction sets that guide production. The processes Paleolithic peoples used to create stone tools, the punch cards that Joseph Marie Jacquard used to direct looms in France in the early 1800s, Henry Ford’s assembly lines, and the blockchains first described by the person (or persons) named Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008: All these are, in Auerswald’s view, examples of code. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:32 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, business history, economic history, economic systems, economics, strategy+business, work

Saturday, March 11, 2017

Regulation, Who Needs It?

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

1:51 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, economic systems, politics, regulation

Monday, January 30, 2017

Private-sector participation in the GCC: Building foundations for success

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

PwC Strategy&, Jan. 30, 2017

The governments of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states have decided to change their economic development model. The state-led approach which relied upon natural resources successfully raised incomes from developing to developed country levels in a little over a generation. However, that model is no longer appropriate as it is undermined by oil dependence, a lack of workforce diversity and skills, a growing need for public services, and insufficient innovation.

One effective response is private-sector participation (PSP). GCC states are already using PSP, but have wielded it tactically and ad hoc. As a result, they have not tapped its full potential. Instead, a comprehensive strategic program of public–private partnerships (PPPs) and privatization initiatives that covers all major sectors of the economy is needed to define a country’s PSP plan. If GCC states can successfully develop, launch, and execute such a PSP program, they can transform their economies. The GCC states could avoid US$164 billion in capital expenditures by 2021 and generate $114 billion in revenues from sales of utility and airport assets alone, and up to $287 billion from sales of shares in publicly listed companies.

Furthermore, GCC states could narrow the innovation gap with other countries, enhance the delivery of and access to government services, and improve their infrastructure. To capture these benefits, GCC governments will need a rigorous and comprehensive approach to PSP and a clearly articulated, long-term implementation plan that encompasses all economic sectors. Such an approach rests on three foundational elements: A governing policy for PSP that is either a standalone policy or part of a broader national policy; a legal framework that encompasses the new laws or modifications to existing laws necessary to facilitate PSP activities; and an institutional setup that clearly defines and allocates authority over PSP to existing government entities or establishes new entities to govern it. Download the white paper here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

5:11 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: articles to ponder, business history, economic systems, economics, entrepreneurship, government

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

John Elkington’s Required Reading

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:28 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, business history, corporate success, economic history, economic systems, entrepreneurship, globalization, innovation

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

A Good Barrel for Bad Apples in Business

strategy+business, November 25, 2015

The business news headlines in the early fall of 2015 read like a scandal sheet. In September, the former owner of Peanut Corporation of America was sentenced to 28 years in prison for knowingly selling contaminated peanut butter that killed nine people and sickened hundreds more. Turing Pharmaceuticals, launched earlier this year by a hedge fund manager, purchased a 62-year-old drug that treats a parasitic infection called toxoplasmosis — the only drug of its kind — and bumped the price from $13.50 per tablet to $750. Volkswagen was coping with the fallout from revelations that engineers may have equipped diesel-powered cars with software aimed at deceiving emissions tests.

We tend to think of the people at companies who engage in such behavior as outliers, the few bad apples that spoil the barrel. But in their new book, Phishing for Phools: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception (Princeton, 2015), George A. Akerlof, Koshland Professor of Economics at University of California, Berkeley, and Robert J. Shiller, Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, argue that we should direct our attention to the barrel instead. The barrel is free markets, which, according to tenets that go back to Adam Smith, are guided by an invisible hand that ensures the individual pursuit of profit is transformed into common good. Unfortunately, that’s not the whole story.

Phishing for Phools is an extension of the authors’ work on how psychological forces can warp markets, as described in their previous book, Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism (Princeton, 2009). The two Nobel Prize–winning economists — Akerlof in 2001 for his work on the market effects of asymmetric information, Shiller in 2013 for his contributions to economic forecasting — define phishing in a broader way than usual. They say it is any activity that entices us to do something that is not in our own interests, but rather in the interest of the “phisherman” (as opposed to the rational behavior assumed in conventional economic theory). They see two kinds of phishing going on in free markets. The first includes emotional and cognitive glitches. A gambling addict who feeds the paycheck needed to feed his family into a slot machine has been legally phished by a casino. The second includes misleading information that is purposely created by the “phishermen.” Investors who received doctored account statements from Bernie Madoff’s firm were illegally phished in this manner.

Whether the phishing is legal or illegal, ethical or unethical, Akerlof and Shiller see it as being driven by the natural operation of free markets: “The free-market equilibrium generates a supply of phishes for any human weakness.” The two authors endeavor to prove this by describing an ongoing epidemic in phishing in a dismayingly wide variety of market contexts: in marketing and advertising; in industries where high-pressure sales tactics are common, such as auto sales, real estate, and credit cards; politics (the market for candidates); food and pharmaceuticals; innovation; tobacco and alcohol; and finance.

You’ll likely be familiar with many of the examples in the book, which are drawn mainly from contemporary inductees into capitalism’s hall of shame: Big Tobacco and its decades-long battle to discredit the link between smoking and cancer, the S&L crisis, the junk bond crisis, the subprime loan crisis. But they are worth rereading in order to understand what they have in common — that is, how and why they are all examples of phishing.

Happily, Akerlof and Shiller identify four obstacles to free-market phishing. There are “standards bearers,” who measure and enforce quality, such as the testing and certification of electronic appliances provided by Underwriters Laboratories. There are “business heroes,” such as Better Business Bureaus (and, presumably, rating sites, like Yelp and TripAdvisor). There are “government heroes” and their legal checks, such as the Uniform Commercial Code, and also “regulator heroes” like the Food and Drug Administration.

Unhappily, however, phishing continues, and the power of those who resist it is constantly being undermined by phishermen in search of larger hauls. As a case in point, the authors offer up the sad tale of the bond ratings agencies, whose cooptation by bond issuers resulted in reckless and inflated estimates that supported and intensified the explosion of subprime mortgages during the housing boom of the 2000s.

Phishing for Phools doesn’t offer much in the way of solutions. “The free market may be humans’ most powerful tool. But, like all very powerful tools, it is also a two-edged sword,” Akerlof and Shiller write. “That means that we need protection against the problems.” However, the only protection they prescribe is a greater recognition among economists of free-market phishing — a recognition that “it is inherent in the workings of competitive markets.” That would be a good a thing, I guess. But economists could debate the merits of this thesis until the end of time, and the rest of us would still be taken for phools.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

10:46 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, business history, economic history, economic systems, economics

Saturday, May 2, 2015

Why King Charles lost his head

Saumitra Jha: How Financial Innovation Helped Start the English Civil War (and Why That’s Important Today)

The question of why Parliament rebelled against Charles has attracted intense interest in the four centuries since. Most historians point to three causes for the revolt in England: overly greedy monarchs, the emergence of a commercial middle class, and the religious struggle accompanying the rise of Protestantism.

The question of why Parliament rebelled against Charles has attracted intense interest in the four centuries since. Most historians point to three causes for the revolt in England: overly greedy monarchs, the emergence of a commercial middle class, and the religious struggle accompanying the rise of Protestantism.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:39 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: articles to ponder, business history, economic history, economic systems, innovation, Insights by Stanford Business, politics

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Soccer and economics

My new book post is up on s+b's blog:

What the Beautiful Game Reveals about the Dismal Science

A lot of people watched the World Cup in Brazil this past month. The final numbers won’t be in for a while, but with record-breaking viewership for the first round of matches and a big bump in the U.S. audience, it’s a good bet that the 2014 Cup eclipsed the more than the 3.2 billion viewers (nearly half the people on earth) who tuned in at some point or another during the 64 matches in 2010. It’s also a good bet that Ignacio Palacios-Huerta, a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is one of very few soccer fans who watched this year’s matches for insights into perverse incentives, market efficiency, and other economic concepts.

A lot of people watched the World Cup in Brazil this past month. The final numbers won’t be in for a while, but with record-breaking viewership for the first round of matches and a big bump in the U.S. audience, it’s a good bet that the 2014 Cup eclipsed the more than the 3.2 billion viewers (nearly half the people on earth) who tuned in at some point or another during the 64 matches in 2010. It’s also a good bet that Ignacio Palacios-Huerta, a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is one of very few soccer fans who watched this year’s matches for insights into perverse incentives, market efficiency, and other economic concepts.What can the beautiful game tell us about the dismal science? As Palacios-Huerta explains in Beautiful Game Theory: How Soccer Can Help Economics (Princeton University Press, 2014), soccer—and indeed many other professional sports—is a terrific laboratory for testing economic theories. “There is an abundance of readily available data, the goals of the participants are often uncomplicated (score, win, enforce the rules), and the outcomes are extremely clear,” he says. “There is an abundance of data, the goals are uncomplicated, and the outcomes are extremely clear.”

Take incentives, for instance. We’re often warned that incentives can have unexpected consequences, but it’s tough to isolate the effects of an incentive—such as stock options, for instance—in the business world. Are senior executives neglecting the long-term well-being of their firms to bump up the value of their options in the short term, or is something else going on? Are managers sabotaging one another to boost their own performance in forced ranking systems or not? That’s tough to prove without a smoking gun, and managerial saboteurs tend not to leave that kind of evidence lying around.

For a more rigorous test, Palacios-Huerta and his colleague Luis Garicano examined the outcomes stemming from a 1994 FIFA rule change in which three points, instead of two, were awarded in round-robin tournaments for a win. (It was an attempt to drive up soccer scores and attract U.S. fans, who presumably find the subtleties of the game far less appealing than a Pelé-style bicycle kick into the net.) In doing so, the economists found empirical evidence for the risks attendant in strong incentive plans.

By analyzing the incidence of dirty play before and after the rule change, they discovered that increasing the points awarded for a win caused a rise in sabotage on the field: fouls and unsporting behavior resulting in yellow cards increased. By analyzing the results of matches, they further determined that the rule change did not change the number of goals scored. Teams played more aggressive offense until they got their first goal, then they hunkered down defensively to protect the win. “The beautiful game became a bit less beautiful,” concludes Palacios-Huerta.

In Beautiful Game Theory, Palacios-Huerta also reports on how he used soccer to prove the long-standing efficient-markets hypothesis—a theory suggesting that in the stock market, for instance, information is processed so efficiently that “unless one knew information that others did not know, no stock should be a better buy than any other.” The problem with proving this hypothesis is that you can’t stop time to analyze the effects of a piece of news on the market. But time does stop in a soccer match.

Palacios-Huerta realized that at halftime, “the playing clock stops but the betting clock continues.” So he identified matches in which a “cusp” goal was scored just before the halftime break, and then analyzed the changes in betting odds during the break at the Betfair online betting exchange. He found that Betfair lived up to its name: “Prices impound news so rapidly and completely that it is not possible to profit from any potential price drift over the halftime interval.”

This is good news for sports bettors, but it’s far less reassuring in light of the New York Times exposé that broke on May 31. It seems that some gamblers are allegedly paying off referees to use penalty calls to rig soccer matches. Efficient or not, when it comes to economic markets, it seems like somebody always knows something that no one else knows.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

5:05 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Academia, books, corporate success, economic systems, economics, sports

Friday, June 20, 2014

Will Chinese demand create global shortages in natural resources?

My no-always-weekly blog post on s+b is up:

Understanding China’s Resource Quest

Much has been written about China’s supersized demand for natural resources—oil and gas, metallic ores, and agricultural commodities—and the effects it could have on the global economy, politics, and the environment. Often these prognostications are suspect: It’s only natural to wonder whether self-interest is skewing a metal trader’s prediction that Chinese demand will drive copper’s price to stratospheric levels or a lobbyist’s prediction that a Chinese company’s acquisition of a U.S. oil company threatens national security.

That’s why I was quite interested in By All Means Necessary: How China’s Resource Quest is Changing the World (Oxford University Press, 2014), a new book written by Elizabeth C. Economy and Michael Levi, senior fellows at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). Economy is an expert on China and author of the seminal book on that nation’s environmental challenges. Levi is an expert in global politics and energy economics. They make for an authoritative team.

The faintly ominous ring of their book’s title notwithstanding, Economy and Levi are dispassionate and evenhanded. Contrary to many experts, they find that, by and large, China is not trying to secure the resources it needs by buying up ore deposits and oil fields—actions that could lead to a stranglehold on vital material. Instead, it is procuring natural resources mainly through trade. This has contributed to radical price increases and more competitive markets. But, according to the authors, further natural resource price shocks are unlikely because the markets have adjusted to Chinese demand.

In response to political fearmongering, Economy and Levi conclude that “the impact of China’s resource quest on international politics and security has been modest thus far.” They admit that China’s willingness to trade with nations like Iran has “helped blunt the impact of Western sanctions.” But they do not find that China has contributed to wars, like the one waged in the Sudan, where China’s state-owned oil company CNPC plays an instrumental role in extracting and refining oil and where 50 percent of the oil produced annually is exported to China.

The authors are less sanguine about the environmental effects of China’s resource needs, mainly because the same challenges that the nation faces domestically are present when it tries to obtain natural resources overseas. When Chinese companies seek to extract resources in nations with lax environmental regulation, a sort of double whammy can occur because neither party is policing the situation. There is a silver lining though: As Chinese companies interact with other more environmentally responsible multinationals, they are actually improving their practices—either because they’re feeling international pressure to do so, or because they’ve found that being responsible can also be profitable. And with corporate responsibility on the state agenda in China, the authors also expect to see better practices in the overseas ventures of Chinese firms.

The authors of By All Means Necessary also analyze the winners and losers among the main players affected by China’s quest for resources. Resource consumers who must buy in the marketplace will pay more, but the owners of those resources will profit from higher demand. Overseas investors have a major new competitor with which to contend and will need to avoid a “race to the bottom.” Governments, especially the U.S. government, will need to factor China’s resource needs into their actions to maintain their own stockpiles and to avoid igniting resource wars. National security is a two-way street.

None of these conclusions sound particularly dire, especially when you consider that China is simply assuming its place among the rest of world’s most resource-hungry nations. And if you dip back into history and examine the behavior of other nations in their quest for natural resources, such as Belgium in the Congo in the late 1800s and the U.S. and the U.K. in Iran in the 1950s, China looks like a shining exemplar…so far.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, competitive intelligence, economic systems, globalization, politics

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Jeremy Rifkin on tomorrow's jobs

My weekly book post on s+b:

The End of Work, Revisited

Jeremy Rifkin’s controversial prognostications on topics such as beef, biotechnology, and business have been sparking debate for at least 40 years. Who knows how far back they go? I picture a family dinner at the Rifkin home circa 1955: Jeremy’s dad, Milton (a manufacturer of plastic bags) is sitting at the head of table, his forkful of pot roast frozen midair, as his 10-year-old son tells him that the family business is going to destroy capitalism.

Rifkin the Younger’s new book, The Zero Marginal Cost Society: The Internet of Things, the Collaborative Commons, and the Eclipse of Capitalism (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014), weaves together many of the threads he has pulled over the years. It is the futurist’s most comprehensive inquiry into business and work yet, and it is built on a thesis that we’ve heard before: Capitalism is tottering and will not last out this century, a victim of “the dramatic success of the very operating assumptions that govern it.” Rifkin says that capitalism’s downfall is inevitable because of its ceaseless quest for productivity and the ever-growing sophistication and power of digital technology. The collision of these two forces is driving down the marginal cost of producing additional units of anything and everything to near zero, a process that will squeeze profits until they scream. (You can hear the argument in more detail here.)

This driving down of marginal cost includes the cost of human labor. Reprising the theme of his book, The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era (Tarcher/Putnam, 1995), Rifkin explains that digitization is replacing jobs. This creates a situation that economists once assumed could not happen: Productivity will rise, but employment will fall.

Twenty years ago, Rifkin’s argument was tinged with foreboding: How, after all, would people survive without jobs? But in The Zero Marginal Cost Society, he is far more optimistic. When I asked him why, he said, “There are a few reasons that I am more optimistic today than I was in 1995. First, the nonprofit sector—the social commons—has been growing even faster than I had envisioned. Between 2000 and 2010, after adjusting for inflation, nonprofit revenues in the U.S. grew by a striking 41 percent, more than double the growth in GDP, which increased by only 16.4 percent.

“The nonprofit community is also the fastest-growing employment sector, outstripping both the government and private sectors in many countries. There are currently 56 million workers employed in the nonprofit sector in 42 countries, and in many of the most advanced industrial countries—including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada—employment in this sector now exceeds 10 percent of the workforce, and its trajectory has been rising year over year since 1995. During the Great Recession (2007–09), the nonprofit sector gained jobs at an average rate of 1.9 percent annually, while the private sector lost jobs at a rate of 3.7 percent.

“Second, the creation of social enterprises, some 35 percent of them nonprofits, has mushroomed in recent years thanks to a new generation of entrepreneurs. There are several hundred thousand social enterprises in the United States that employ over 10 million people and that have revenues of US$500 billion per year. These enterprises represented approximately 3.5 percent of the nation’s GDP in 2012.

“Third, what makes the social commons more relevant today than at any other time in its long history is that we are now erecting a high-tech global technology platform—the Internet of Things (IoT)—whose defining characteristics could support and nurture it. The IoT facilitates collaboration and the search for synergies, making it an ideal technological framework for advancing the social economy. Its operating logic optimizes lateral peer production, universal access, and inclusion, and its purpose is to encourage a sharing culture. The IoT will bring the social commons out of the shadows, giving it a high-tech platform to become the dominant economic paradigm of the 21st century.”

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

1:39 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, business history, corporate success, economic systems, innovation, personal success

Wednesday, January 22, 2014

Capitalism's dotage

My weekly book post on s+b's blog covers a book that suggests that business as usual wont be an option much longer:

Does Capitalism Have a Future? (Oxford University Press, 2013). It’s likely that the WEF attendees will end up in a place similar to the sociologists—with a general consensus that the global economy is facing huge challenges, conflicting views about their causes and consequences, and only speculative guesses about possible solutions.

Leading the batting order of solo essays (which are sandwiched between an introduction and conclusion written by the entire author team), Yale senior research scientist and former International Sociological Association president Immanuel Wallerstein asserts that capitalism is approaching a “structural crisis much bigger than the recent Great Recession.” This crisis, he says, will come from a profit squeeze caused by an inexorable rise in the prices of labor and raw materials, and tax rates, combined with political instability. Randall Collins, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, thinks that the primary driving force behind this instability will be the gutting of the middle class as up to two-thirds of the jobs that support it disappear... read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:31 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, economic history, economic systems