strategy+business, October 16, 2020

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Yagi Studio

If you’re a foodie, the research that Vaughn Tan undertook to write The Uncertainty Mindset will strike you as a dream gig. The assistant professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at University College London’s School of Management spent much of the past decade studying — and embedded within — the culinary R&D teams associated with a handful of the world’s top purveyors of high-end cuisine, including José Andrés’s ThinkFoodGroup, Nathan Myhrvold’s Modernist Cuisine, Heston Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck, René Redzepi’s Noma, and “Amaja” (a pseudonym Tan uses for a restaurant that sounds a lot like Poul Andrias Ziska’s Koks). Aside from the good eats, Tan came away from his research with unconventional ideas for structuring and stimulating innovation teams.

The innovation challenge facing these rarefied culinary organizations is daunting; the customer expectations of an Apple or a Tesla pale by comparison. Imagine trying to satisfy a discerning gourmand who has waited a year for a reservation and then traveled from Singapore to the Faroe Islands solely for an 18-course meal. It is expected to be one of the best meals in the world. Each course features unusual ingredients prepared in unique ways that not only engage the senses but also impart the identity of the chef and the restaurant, so much so that it couldn’t have come from any other kitchen. Tan calls this elusive quality familiar novelty. “Novelty combined with distinctive familiarity makes for loyal customers — and is nearly impossible to copy,” he writes.

Outside London, at The Fat Duck Experimental Kitchen (FDEK), Tan observes pastry chef Isabel Rodriguez as she creates a dessert that will anchor an entirely new menu. “The team had decided that it would have to convey the feeling, as Rodriguez said, of being ‘dreamy, comforting, surreal. Like how you feel when you are about to fall asleep when you’re small. You’ve been bathed, and you’re feeling clean and tired, and everything smells like baby powder,’” writes Tan. Before the work is done, the dish, which the team calls Counting Sheep, will evolve into two dishes served in quick succession. Among its many fine details is the design and fabrication of a spoon with a fuzzy handle that will be dusted lightly with, yes, baby powder.

At Amaja, the R&D team spends three months figuring out how to cook 200-year-old mahogany clams — an ingredient never before used in high cuisine. In ThinkFoodGroup’s first Las Vegas venture, the company takes on the high-pressure work of launching three restaurants — serving tapas, Chinese–Mexican food, and a tasting menu — on the opening night of a newly constructed gaming resort.

In observing how culinary R&D team members work individually and together on such projects, Tan uncovers six “innovation insights” that serve as the core findings of his book. Two of the insights are particularly intriguing. Read the rest here.

Friday, October 16, 2020

Uncertainty on the menu

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:20 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, creativity, innovation, org culture, strategy+business

Sunday, January 5, 2020

The Galvanizing Effect Of The Social Enterprise In Action

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

Forbes, December 27, 2019

by Michael Gretczko

photo: GETTY

I love seeing how the blue water of the Caribbean meets the white sands of Puerto Rico from the air. In October, after landing, I didn’t go to the beach. Instead, I headed into downtown San Juan, where I joined 22 of my colleagues — all just a few years out of school and eager to make a difference not only in our organization, but also in people’s lives in the world at large.

They were in San Juan to participate in our Human Capital People to People (P2P) program; I was there to support them as an advisor and mentor. P2P is a skills-based volunteering initiative where our junior professionals undertake an intensive week-long pro bono engagement to support local nonprofit organizations. As with all of our volunteering programs, we were there to bring our greatest asset — the skills and experience of our people — to help nonprofits address their most critical issues and help drive transformational outcomes.

For me, the week in San Juan was a firsthand example of the benefits that a social enterprise can generate. At Deloitte, we define the social enterprise as a company whose mission combines revenue growth and profit-making with the need to respect and support its environment and stakeholder network. It is a business that embraces its responsibility to the community and serves as a role model to other organizations and its people.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

2:28 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: change management, corporate life, corporate success, creativity, employee experience, management, nonprofits, personal success

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

The Greatest Showman on Earth

strategy+business, August 14, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

Phineas Taylor Barnum’s future was bright. He believed from the age of 4 that his grandfather, pleased to have his grandson as his namesake, had purchased the most valuable farm in Connecticut in Barnum's name. For years, the boy’s grandfather talked about the farm and his neighbors congratulated him on being the richest child in the town of Bethel. At the age of 12, Barnum was taken to see his farm. It was five worthless, inaccessible acres in a large swamp. Everyone had a great laugh.

Phineas Taylor Barnum’s future was bright. He believed from the age of 4 that his grandfather, pleased to have his grandson as his namesake, had purchased the most valuable farm in Connecticut in Barnum's name. For years, the boy’s grandfather talked about the farm and his neighbors congratulated him on being the richest child in the town of Bethel. At the age of 12, Barnum was taken to see his farm. It was five worthless, inaccessible acres in a large swamp. Everyone had a great laugh.

Robert Wilson, editor of the American Scholar and author of Barnum, sees the roots of the 19th-century American showman’s outsized pecuniary drive in “this strangely cruel and astonishingly drawn-out joke.” But it’s hard to judge whether the story is true — the only citation Wilson offers is Barnum’s autobiography, which should give the reader pause, considering its author’s reputation for humbug and penchant for spinning his own life story.

If Barnum didn’t stretch the story (or invent it outright), it also may reveal the roots of his preternatural talent for hucksterism. Certainly, he elevated the joke to unprecedented heights with a series of frauds so entertaining to American and European audiences of every social class that instead of shunning him, they rewarded him with riches that beggared the promise of the farm that never was. He also provided an early and, sadly, enduring lesson in the use of brazen hype, shameless self-promotion, and fake news as the basis of a successful business. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

3:06 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, creativity, customer experience, entrepreneurship, marketing, personal success, strategy+business

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Large businesses don’t have to be lousy innovators

strategy+business, April 11, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Kanchisa Thitisukthanapong

Gary Pisano, author of Creative Construction: The DNA of Sustained Innovation, doesn’t buy the idea that large enterprises are inherently lousy innovators. Back in 2006, Pisano, the Harry E. Figgie Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, traced the origin of every drug approved by the FDA over a 20-year period to either one of the world’s 20 largest pharmaceutical companies or one of the 250 smaller, supposedly more innovative biotechs. When he compared the two groups, he discovered a “statistical dead heat” — R&D productivity was no better in the smaller biotechs than in big pharma.

Pisano also points to anecdotal evidence to support his opposition to the conventional wisdom about innovation in large enterprises. For every big, established company that failed at transformational innovation (think Blockbuster, Kodak, and Polaroid), he points to another that has succeeded. In 1964, when IBM announced its revolutionary 360 mainframe computers, it was already the largest computer company in the world and ranked 18th on the Fortune 500. In 1982, when Monsanto scientists invented the foundational technology for GMOs (genetically modified organisms), the company was 81 years old and number 50 on the Fortune 500. And in 2007, when Apple launched the iPhone, it had sales of US$24 billion and already stood at 123rd on the Fortune 500.

Pisano says that the difference between a Blockbuster and an IBM is the ability of leaders to sustain and rejuvenate the innovation capacity of their companies. It’s an ability he calls “creative construction,” and he writes that it “requires a delicate balance of exploiting existing resources and capabilities without becoming imprisoned by them.”

Walking that tightrope is a challenge for large companies. It’s tough to move the needle with innovation when the needle’s scale is measured in billions of dollars. “For J&J [Johnson & Johnson] to maintain its historical rate of top-line growth,” reports Pisano, “it must generate about $3 billion–$4 billion of new revenue per year.” The complexity of managing innovation in large organizations can also be daunting. “When you get to be the scale of a J&J, you have a lot of moving parts,” he explains. “You now have a system with serious frictions. Friction impedes mobility. Lack of mobility means lack of innovation.”

But large companies also have some advantages that can give them a leg up in innovation. “Larger enterprises like J&J have massive financial resources to explore new opportunities,” says Pisano. They can hedge their bets, tap deep reservoirs of talent, navigate regulatory agencies, and use their huge distribution networks and strong brands to roll out new products to millions of existing customers. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:53 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, corporate success, creativity, innovation, leadership, org culture, strategy+business

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

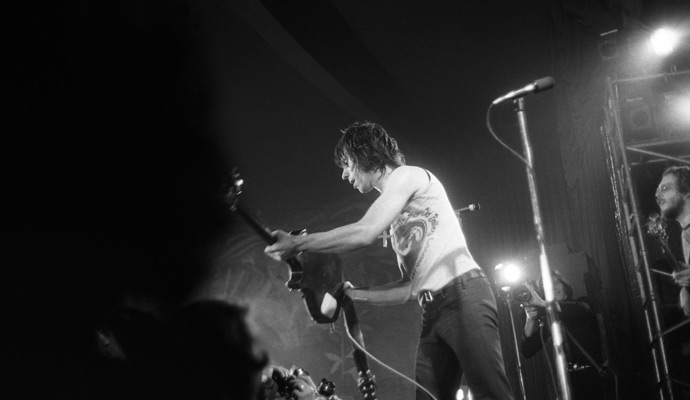

Leadership lessons from a guitar hero

strategy+business, March 19, 2019

by Theodore Kinni

About an hour into Still on the Run, a documentary exploring the career of rock guitar god Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, another deity in the pantheon, pops up on screen and says, “I don’t even know how he’s doing it half the time.” Clapton is talking about Beck’s ability to give voice to the guitar. But his comment set me to wondering how Beck developed his unique style and what, if any, lessons his nearly 60-year career might offer those who aspire to reach the top of the business world.

With CEO tenure in large companies running five years or so, the fact that Beck has been numbered among the world’s best guitarists for about 10 times that long is worth exploring. Surely, innate talent and endless hours of practice count for a lot. But loads of guitarists have both, and haven’t had careers that lasted as long as the average CEO’s. Beck, however, has been an inveterate seeker of innovation in both technology and technique. And this habit has enabled the 74-year-old London-born musician to continuously expand his capabilities and transform his sound.

Jeff Beck performs at the Bataclan in Paris in 1973.

Photograph by Philippe Gras / Alamy

As biographer Martin Power tells it in Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck (Omnibus Press, 2014), Beck’s parents valued musicianship, but not the electric guitar, which in the 1950s was associated with rockabilly and other disreputable musical genres. When his parents refused even to spring for new strings for a borrowed guitar, the teenager began building his own crude instruments. Unable to tune his early efforts, Beck learned to bend the strings to pitch while playing, a work-around that became a signature. The wannabe lead guitarist stole the pickup needed for his first electric guitar and built its amp in his school’s science department. Since then, Beck continually explored and adopted technological advances in guitar effects and electronics — such as tape-delay units, fuzz boxes, and guitar synthesizers — to shape and extend his playing.

Beck’s eagerness to learn and incorporate techniques from far-flung places is another hallmark of his career. Like Clapton, he learned from American blues giants — and rode the wave of cultural appropriation that gave rise to rock and roll. According to Power’s biography, Beck says that the first time he heard Jimi Hendrix play, he thought, “Oh, Christ, all right, I’ll become a postman.” Then he followed Hendrix around to learn how he created his sound. Other inspirations include a women’s choir that recorded Bulgarian folk songs, operatic tenor Luciano Pavarotti, and electronic dance music. Beck describes his resulting style as “a form of insanity…. A bit of everything, really. Rockabilly licks, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, all the people I’ve loved to listen to over the years. Cliff [Gallup], Les [Paul], Eastern and Arabic music, it’s all in there.” Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

9:12 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: creativity, innovation, leadership, personal success, strategy+business, work

Tuesday, December 11, 2018

Grow Faster by Changing Your Innovation Narrative

Learned a lot editing this one:

MIT Sloan Management Review, December 10, 2018

by George S. Day and Gregory P. Shea

An innovation narrative is an oft-overlooked facet of organizational culture that encapsulates employees’ beliefs about a company’s ability to innovate. It serves as a powerful motivator of action or inaction. We find innovation narratives in two basic flavors: growth-affirming and growth-denying, or some combination thereof.

Companies that lead — or aspire to lead — their industries in organic growth need to have a coherent, growth-affirming innovation narrative in place, and we will discuss why that’s important and what it can look like. But what actions support the development and maintenance of such a narrative? To answer that question, we tested 18 possible innovation levers and identified the four that are most relied upon by organic growth leaders to stay ahead of their competitors: (1) invest in innovation talent, (2) encourage prudent risk-taking, (3) adopt a customer-centric innovation process, and (4) align metrics and incentives with innovation activity. We will look at each one in turn.

These four levers will be familiar to innovation practitioners, but their effects intensify with managerial focus. They serve as so-called simple rules. That is, they avoid the confusion and dilution of effort that result from trying to pull too many levers at once or in an uncoordinated manner, and they channel and prioritize leaders’ efforts to embed a growth-affirming innovation narrative in their companies. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:46 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: articles to ponder, corporate success, creativity, innovation, management

Tuesday, September 11, 2018

Why design thinking is now an essential capability for HR (and how to adopt it)

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

InsideHR, September 10, 2018

by Jeff Mike

HR is undergoing a fundamental shift. The rigid, policy-driven programs and processes of yesterday, which were primarily focused on compliance, efficiency, and conventional approaches to talent management, are giving way. Leading HR practitioners are replacing top-down programs and processes with more agile, worker-centric offerings – offerings that are personalised for employees and that are informed by a robust understanding of work and workforce segments – and design thinking can play an important role in this process.

Bersin research backs this up, and high-performing HR organisations are 3.5 times more likely to focus relentlessly on user experience when designing HR offerings than lower-performing organisations. This is a significant finding: High-performing HR organisations are also associated with a host of positive business outcomes, such as meeting or exceeding financial targets, improved processes, greater responsiveness to change, and enhanced innovation. It is also why design thinking is becoming an essential HR capability.

A design thinking mindset can drive results

- User-centered design, which places the employee at the heart of the design;

- Human-centered design, which ensures that the design speaks to the emotions of users;

- Soft systems methodology, which ensures that multiple, divergent perspectives are incorporated into the design process.

A global leader in consumer transaction technologies used design thinking to address high rates of employee attrition, especially among new hires and key worker categories, such as customer engineers. It developed and used its new employee experience model to rebuild its onboarding process. The result: the volume of new hires who left dropped by 22 per cent, resulting in a savings of $7 million. In addition, turnover within the critical customer engineer segment fell from 34 per cent to 10.9 per cent...read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:44 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: corporate success, creativity, human resources, innovation, management, org culture, work

Thursday, August 23, 2018

When Prediction Gets Cheap

strategy+business, August 8, 2018

strategy+business, August 8, 2018

by Theodore Kinni

I don’t usually write mash notes, but I recently sent one to Waze via Twitter. I figured the navigation app had helped me avoid more than 100 hours of traffic jams over a couple of years, and I felt compelled to declare my undying gratitude.

After reading Prediction Machines, by three Rotman School of Management professors, it turns out I’m not so much enamored with Waze as I am with the technology that powers it: artificial intelligence (AI). It is AI that enables the app to predict the best routes for its users.

According to Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb, who are also, respectively, founder, chief economist, and chief data scientist of the Creative Destruction Lab, prediction is the essential output of AI. “The current generation of AI provides the tools for prediction and little else,” they write. “Today, AI tools predict the intention of speech (Amazon’s Echo), predict command context (Apple’s Siri), predict what you want to buy (Amazon’s recommendations), predict which links will connect you to the information you want to find (Google search), predict when to apply the brakes to avoid danger (Tesla’s Autopilot), and predict the news you will want to read (Facebook’s newsfeed).”

This is the key insight of Prediction Machines, and it is an extraordinarily useful one for any executive who has been grappling with the implications and ramifications of AI. AI will automate prediction, and as a result, prediction will become cheap. “Therefore, as economics tells us,” explain the authors, “not only are we going to start using a lot more of it, but we are going to see it emerge in surprising new places.” Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

10:13 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: AI, analytics, artificial intelligence, bizbook review, books, corporate success, creativity, innovation, strategy+business, technology

Friday, May 11, 2018

An Ode to the Thief of Time

strategy+business, May 11, 2018

by Theodore Kinni

In late 1934, a department store magnate named Edgar Kaufmann engaged Frank Lloyd Wright to design a weekend home in the woods an hour or so southeast of Pittsburgh. It was a huge boon for Wright — his reputation had waned, commissions had dried up in the Depression, and his home and studio were threatened with foreclosure. The architect visited the Kaufmann site, asked for a survey, and then, the story goes, didn’t do a damn thing.

In late 1934, a department store magnate named Edgar Kaufmann engaged Frank Lloyd Wright to design a weekend home in the woods an hour or so southeast of Pittsburgh. It was a huge boon for Wright — his reputation had waned, commissions had dried up in the Depression, and his home and studio were threatened with foreclosure. The architect visited the Kaufmann site, asked for a survey, and then, the story goes, didn’t do a damn thing.Nine months later, Kaufmann unexpectedly visited Wright’s studio to look at the design for his new home, which, he had been told, was progressing beautifully. Wright reportedly put pencil to paper for the first time. Two hours later, he presented Kaufmann with a plan for Fallingwater, an acknowledged masterpiece of residential architecture.

“The only way to explain the nine months Wright spent not working on Fallingwater is by procrastination’s perverse logic. Nothing was the only thing that could be done in such a situation,” writes Andrew Santella in Soon, his engaging, meandering, and, of course, overdue exploration of the behavioral tic...read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

11:23 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, creativity, human resources, management, strategy+business, work, writing

Saturday, May 5, 2018

If You Cut Employees Some Slack, Will They Innovate?

MIT Sloan Management Review, May 4, 2018

by Yasser Rahrovani, Alain Pinsonneault, and Robert D. Austin

Given the significant investment that slack-based innovation programs require, the decision to adopt one shouldn’t be made off the cuff. But what are the factors underlying that decision and how should such programs be designed? To begin to answer these questions, we conducted in-depth interviews of knowledge workers in different industries to understand what motivated them to take risks and explore new ideas, and, more specifically, whether and how slack resources might have contributed to their innovativeness. We then created and refined an empirical model based on the factors and relationships that appear to influence employee innovation and tested it using a sample group consisting of 427 employees from North American companies.

We found that different types of employees respond in different ways to slack innovation programs; that different kinds of slack resources are better suited to certain types of employees than they are to others; and that different kinds of slack innovation programs produce different kinds of innovation. Companies can use these findings to design more effective slack innovation programs and maximize their returns on slack resources...read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

2:45 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: articles to ponder, corporate success, creativity, innovation, management, org culture, work

Saturday, March 10, 2018

Seven Technologies Remaking the World

Learned a lot lending an editorial hand here:

MIT Sloan Management Review, March 9, 2108

by Albert H. Segars

This report provides executives with a lexicon to the revolution. It identifies seven core technologies — pervasive computing, wireless mesh networks, biotechnology, 3D printing, machine learning, nanotechnology, and robotics — and describes their implications for commerce, health care, learning, and the environment. Use it as a guide and a basis for strategic discussion as you and your team seek to understand today’s business frontiers and the opportunities that lie ahead.

Seven Technological Sparks

“You’re only given one little spark of madness,” said the late actor and comedian Robin Williams. “You mustn’t lose it.” Williams used his spark to ignite his comedic rocket and blast past the established boundaries of his craft. Technology provides a similar spark: It enables us to push beyond the established boundaries of our world.

The mechanized spinning of textiles, large-scale manufacturing of chemicals, steam power, and efficiencies in iron-making sparked the first Industrial Revolution (1760-1840). Railroads, the telegraph and telephone, and electricity and other utilities sparked the second Industrial Revolution (1870-1940). Radio, aviation, and nuclear fission sparked the Scientific/Technical Revolution (1940-1970). The internet and digital media and devices sparked the Information Revolution (1985-present). In each instance, the inflection point that marked the new revolution was the appearance of new technologies that fundamentally reshaped key aspects of the world, such as commerce, health care, learning, and the environment.

Today, we see technological sparks everywhere. They are emerging from the digital, chemical, material, and biological sciences, and they are precipitating a revolution that is altering nearly every dimension of our lives.

But what are the dominant technologies driving this revolution? And how will they shape and reshape the world of commerce — and the world at large? These are critical questions for executives, and the answers will determine how value will be defined in the future, how businesses will be structured and managed, and where new opportunities for profitable growth may lie.

To help executives answer these questions, I conducted two surveys of veteran technology entrepreneurs working in companies in a variety of sectors, analyzed the results, and then developed and assessed the validity of the findings in a series of individual interviews and field visits. The study revealed seven classes of technology that are driving today’s universal revolution: pervasive computing, wireless mesh networks, biotechnology, 3D printing, machine learning, nanotechnology, and robotics.

Each of these technology classes exhibits three distinctive and rapidly evolving capabilities that are significantly different, more advanced, and larger in scope than the technologies of past revolutions. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

12:36 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: competitive intelligence, corporate success, creativity, digitization, entrepreneurship, innovation, leadership, personal success, strategy, sustainability, technology

Wednesday, February 21, 2018

How to Get Time on Your Side

strategy+business, Feb. 21, 2018

by Theodore Kinni

The vagaries of time can be bewildering. One day, you drive through heavy traffic as if in a perfectly choreographed dance number; the next, it feels as if you’ve entered a demolition derby. One day, you’re brimming with ideas; the next, your creativity well is as dry as Death Valley. Timing is everything, right?

Actually, no. That’s what Daniel Pink declares in the last sentence of his illuminating and often surprising new book, When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing. “I used to believe that timing is everything,” he writes. “Now I believe that everything is timing.”

What Pink means is that there are predictable oscillations present in the days of our lives, and in individual and group work, that affect the outcomes we are working toward. In When, he argues that we can improve our chances of success in work and life if we simply recognize these oscillations and use them to our advantage. This may seem akin to casting runes, but in his trademark style, Pink supports his thesis with a convincing and nuanced reading — and synthesis — of a wide variety of scientific research.

Much of the research that Pink offers stems from the application of big data and analytics. Take, for instance, the study of 26,000 earnings calls from 2,100 companies over a span of six and a half years conducted by three business professors. They discovered that the tenor of calls and their effects on stock price are related to the hour in which they are held. Calls made first thing in the morning tended to be positive. Call results declined until lunchtime, when there was a small bounce, and then declined again until after the closing bell. (What time is your next earnings call?) Read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

11:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, change management, corporate success, creativity, decision making, management, personal success, strategy+business, work

Monday, February 19, 2018

The Power of a Free Popsicle

Insights by Stanford Business, Feb 19, 2018

by Theodore Kinni

Los Angeles boasts plenty of terrific hotels. At this writing, the top three on TripAdvisor are the Beverly Hills Hotel, Hotel Bel-Air, and the Peninsula Beverly Hills. If you can get a room at any of them for under $700 per night, TripAdvisor says you’re getting a “great value.”

Los Angeles boasts plenty of terrific hotels. At this writing, the top three on TripAdvisor are the Beverly Hills Hotel, Hotel Bel-Air, and the Peninsula Beverly Hills. If you can get a room at any of them for under $700 per night, TripAdvisor says you’re getting a “great value.”The fourth name on the list is the Magic Castle Hotel. You can snag a room there for $199, but TripAdvisor doesn’t call that out as a great rate. The Magic Castle Hotel, as Chip Heath, the Thrive Foundation for Youth Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, describes it, “is actually a converted two-story apartment complex from the 1950s, painted canary yellow … [with] a pool that might qualify as Olympic size, if the Olympics were being held in your backyard.”

How does the Magic Castle Hotel maintain such an enviable TripAdvisor ranking among the 355 hostelries it lists in LA? In their new book, The Power of Moments, Heath and his brother, Dan Heath, a senior fellow at Duke University’s CASE Center, trace it to the hotel’s ability to create “defining moments.” These moments, they say, are ones that bring meaning to our lives and provide fond memories.

One of those defining moments is the Popsicle Hotline. Visitors at the hotel’s pool can pick up a red phone on a poolside wall to hear, “Hello, Popsicle Hotline.” They request an ice-pop in their favorite flavor, and a few minutes later, an employee wearing white gloves delivers it on a silver platter, no charge. It’s a small defining moment that doesn’t cost much to produce, but has paid off for the Magic Castle Hotel.

In The Power of Moments, the Heath brothers identify four metatypical defining moments. Elevation moments transcend ordinary experience, like the arrival of an ice-pop on a silver platter. Insight moments rewire our understanding of the world, like George de Mestral pulling burrs from his clothes after a hike and getting the idea for a new kind of fastener that he named Velcro. Moments of pride accompany achievement, which is why employee recognition is such a powerful tool. And moments of connection — like weddings, graduations, and retirements — strengthen relationships. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

11:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, corporate success, creativity, customer experience, entrepreneurship, innovation, Insights by Stanford Business, org culture, personal success

Wednesday, December 13, 2017

How to Break Bad Business Habits

strategy+business, December 13, 2017

by Theodore Kinni

Back in the day, reading the newspaper on my morning commute to Manhattan was an origami-like exercise in folding and refolding. I never wondered why newspapers were printed on broadsheets that were too big for the bus. But Freek Vermeulen did. The clumsily sized standard for newspapers of record peeved him.

Back in the day, reading the newspaper on my morning commute to Manhattan was an origami-like exercise in folding and refolding. I never wondered why newspapers were printed on broadsheets that were too big for the bus. But Freek Vermeulen did. The clumsily sized standard for newspapers of record peeved him.It took the associate professor of strategy and entrepreneurship at the London Business School years to ascertain that the widely used broadsheet dated back to 1712. That’s when the English government began taxing newspaper owners by the number of pages they printed. Bigger pages meant fewer pages and thus less tax. The tax was eventually abolished, but the broadsheet remained the standard — even though the cost of the paper was high and its unwieldy handling irritated readers such as Vermeulen.

In 2003, an English newspaper bucked the long-established standard. The struggling Independent ran an experiment. It offered its paper in broadsheet and in a format exactly half that size in one market. The smaller paper outsold the larger by three to one. The Independent’s leaders quickly adopted the half-size version nationwide, and the paper’s print circulation rose 20 percent annually for several years.

The lesson, says Vermeulen, and the worthy theme of his new book, Breaking Bad Habits: “Killing bad practices can open up new avenues of growth and innovation and reinvigorate your business.” Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, corporate success, creativity, innovation, management, personal success, strategy+business

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Take a Timeout, Leaders

strategy+business, October 11, 2017

strategy+business, October 11, 2017by Theodore Kinni

On July 4, 1845, Henry David Thoreau went to the woods to live deliberately. After spending two years, two months, and two days in a 150-square-foot cabin that he built himself for $28.12 and a halfpenny, Thoreau had worked out the gist of the transcendentalist classic Walden; or, Life in the Woods. In it, he wrote, “I never found the companion that was as companionable as solitude.”

CEOs and other leaders would do well to get on companionable terms with solitude, too, according to first-time authors Raymond M. Kethledge, a U.S. Court of Appeals judge, and Michael S. Erwin, a leadership development consultant and assistant professor at West Point. Leaders don’t necessarily have to get off the grid and live in a hut for two years. But in Lead Yourself First, the authors make an extended argument that leaders should reserve some alone time “to find clarity, creativity, emotional balance, and moral courage.” They illustrate their thesis with numerous examples. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

10:25 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, corporate success, creativity, decision making, entrepreneurship, leadership, management, personal success, strategy+business

Wednesday, August 2, 2017

A Goldilocks Approach to Innovation

by Theodore Kinni

In 2008, when Nike executive Sarah Robb O’Hagan was tapped to lead Gatorade, the sports drink’s sales were in decline and it was losing market share to its principal rival, Powerade. She couldn’t turn to incremental innovation: Pursuing the tried-and-tested strategy of adding flavors and low-calorie options to the Gatorade portfolio had already run its course, and was not yielding returns. The idea of blowing up one of PepsiCo’s billion-dollar brands and the organization behind it in a bid for radical reinvention was too risky.

What did Robb O’Hagan do? Taking a page from Nike’s playbook, she refocused the company’s attention — and more meaningfully, its product development and marketing budgets — on Gatorade’s core customers: the serious athletes, young and old, who accounted for 46 percent of sales. Then, she began introducing new hydration and nutrition products designed particularly for that core group. Gatorade introduced a series of gels, bars, and protein shakes that complemented the sports drink and drove its sales, instead of cannibalizing demand for it.

“The innovations were diverse, targeted a specific set of customers, and posed little strategic risk,” writes Wharton School professor of practice David Robertson, author, with Kent Lineback, of The Power of Little Ideas. The new products also reversed Gatorade’s sales slide. By 2015, Gatorade, with sales of US$5.6 billion, owned 78 percent of the U.S. market for sports drinks, about four times Powerade’s 19 percent share. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

4:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, business history, corporate success, creativity, entrepreneurship, innovation, leadership, management, strategy+business

Wednesday, July 5, 2017

'Hit 'em Where They Ain't!' and Two More Lessons in Strategy From General Douglas MacArthur

Inc., July 5, 2017

by Theodore Kinni

Seventy-two years ago today, on July 5, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur officially announced the liberation of the Philippines. It was a triumphal moment for the 5-star general. It marked the ultimate fulfillment of his memorable promise ("I shall return"), and it brought the war in the Pacific to Japan's doorstep.

MacArthur was one of the world's most admired leaders in those days, and although the Chinese and President Harry Truman would tarnish his shining reputation in the 1950s, MacArthur's strategic creativity, agility, and focus in World War II's Pacific Theater remain a high point in military history. They also offer valuable lessons to founders who are searching for innovative ways to gain a foothold in highly competitive markets populated by stronger, more established players.

Here are three of those lessons, drawn from No Substitute for Victory: Lessons in Strategy and Leadership from General Douglas MacArthur. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:39 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, corporate success, creativity, leadership, personal success, strategy

Monday, July 3, 2017

Spend Your Weekend Like Shonda Rhimes (Studies Prove It Will Boost Your Productivity)

Inc., July 1, 2017

by Theodore Kinni

"You can work long, hard or smart, but at Amazon.com, you can't choose two out of three," asserted Jeff Bezos in his 1997 letter to shareholders. Journalist Katrina Onstad strenuously disagrees: "Actually, you should choose: the last two. The first one is bullshit."

Onstad makes that case in her new book, The Weekend Effect: The Life-Changing Benefits of Taking Time off and Challenging the Cult of Overwork (HarperOne, May 2017). In it, she cites studies stretching back to the early 1900s that prove that our productivity and effectiveness decline when we consistently exceed 40-hour work weeks. This should give pause to entrepreneurs who think they--and their employees--have to work long hours to succeed.

In fact, Onstad calls out some highly successful founders whose work ethic might give Jeff Bezos pause--like TV producer and showrunner Shonda Rhimes. Rhimes gets as many as 2,500 emails daily, but she won't read or respond to them after 7:00 pm on weeknights or on weekends. "Work will happen twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year if you let it," Rhimes told NPR. "It suddenly occurred to me that unless I just say, 'That's not going to happen,' it was always going to happen."

I interviewed Onstad (on a Wednesday during working hours) to learn more about The Weekend Effect and why and how we should reclaim our weekends. Read the rest here.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, business history, corporate success, creativity, entrepreneurship, human resources, management, org culture, personal success, work

Monday, June 26, 2017

This Treasure Map Launched Disney's $17 Billion Theme Park Business

Inc., June 26, 2017

by Theodore Kinni

On Sunday, June 25, a map of Disneyland sold for $708,000, the highest price ever paid at auction for a piece of Disney memorabilia. It's worth every penny. This is the map that Walt Disney and his brother Roy used to raise the financing needed to build Disneyland. This map launched the parks and resorts business that swelled the coffers of the Walt Disney Company by $17 billion in fiscal 2016.

The map was drawn in September 1953, over a single weekend. As Disney Legend Herb Ryman later recalled, Walt called him on a Saturday morning and asked him to come to the studio. When Herb arrived, Walt explained that he needed $17 million to build Disneyland.

"Gee, that's a lot of money," said Herb. "What's the park going to be like?"

"It's going to have a lot of rides and it's going to have a train," said Walt. "It's going to have a lot of things, a whole lot of things. A lot of people. Very exciting. Roy has got to take a drawing with him on Monday morning to show the bankers. You know the bankers don't have any imagination."

"Well, where are the drawings?" asked Herb. "I'd like to see them."

"Oh, you're going to make them," said Walt. Read the rest here

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:49 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: books, business history, corporate success, creativity, entrepreneurship, innovation, leadership

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Train Your Brain To Focus. It'll Make You a Better Leader

Inc., May 11, 2017

The "Invisible Gorilla" experiment is often cited as one more lesson in the many facets of cognitive failure. But Friederike Fabritius and Hans W. Hagemann of Munich Leadership Group argue that a sharp, strong focus is an essential trait and strength of leaders.

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

7:36 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bizbook review, books, creativity, leadership, personal success, work