strategy+business, May 25, 2021

by Theodore Kinni

Photograph by Jeremy Horner

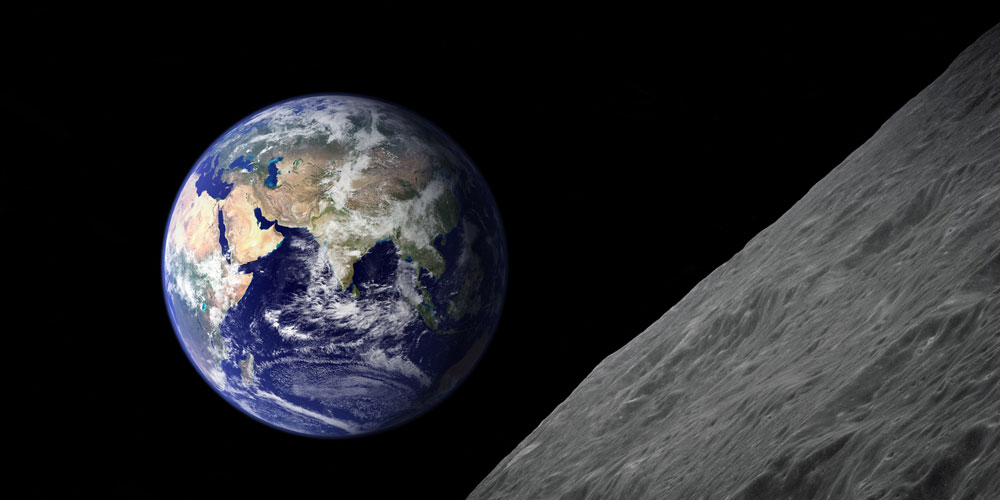

NASA has set its sights on Mars. In April, the space agency flew a solar-powered drone on the red planet — the first powered flight on another world. A month earlier, it successfully fired up the four engines of its most powerful rocket since the Apollo era. If the funding and political will can be sustained, this will be the rocket that lifts humans to Mars. James Edwin Webb would surely be delighted.

Webb was NASA’s second administrator, appointed by President John F. Kennedy in January 1961. He led the agency through the early manned flights of the Mercury and Gemini programs and set the course for the Apollo lunar missions. Webb resigned in October 1968, 18 months after three astronauts died in a cabin fire during a launch rehearsal for the first mission of the Apollo program. His resignation came just a few days before the program successfully resumed with Apollo 7, and less than a year before Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon.

Kennedy chose Webb because, as Tom Wolfe wrote in The Right Stuff, “he was known as a man who could make bureaucracies run.” Webb’s CV included private- and public-sector leadership. He had advanced from personnel director to treasurer to vice president at the Sperry Gyroscope Company, as it grew from 800 to 33,000 employees, and served as president of the Republic Supply Company, a troubled business that its parent, Kerr-McGee Oil Industries, sold at a profit thanks to his leadership. In the public sector, President Harry S. Truman appointed Webb director of the Bureau of the Budget, and then, undersecretary of state to Dean Acheson. “I do not know any man in the entire United States, in the government or out of the government, who has a greater genius for organization, a genius for understanding how to take a great mass of people and bring them together,” said Acheson of Webb.

In January 1961, when the call came to lead NASA, Webb tried to avoid it. He refused meetings with Kennedy’s science advisor and turned down a direct job offer from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. But when Webb found himself face-to-face with Kennedy, he was unable to refuse the insistent president. As if to eliminate any chance that Webb might yet escape, Kennedy promptly marched his new administrator from the Oval Office to the White House press office, where the appointment was announced to the media. The keystone of NASA’s executive team, a man whom the New York Times would call an “extraordinary manager,” was in place.

Webb and his achievements at NASA are not as well-known as they should be. The intense interest in the astronauts and their exploits, the Apollo 1 tragedy, and the passage of time have obscured his role in the first era of the space age. But there are useful lessons in it for today’s leaders. Read the rest here.

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Moonshot management

Posted by

Theodore Kinni

at

8:43 AM

![]()

Labels: aviation, corporate success, decision making, government, leadership, management, NASA, strategy+business

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment